Welcome to Close Reads! In this series, Leah Schnelbach and guest authors will dig into the tiny, weird moments of pop culture—from books to theme songs to viral internet hits—that have burrowed into our minds, found rent-stabilized apartments, started community gardens, and refused to be forced out by corporate interests. This time out, writer and cultural critic Sarah Welch-Larson knits a colorful tale of fandom, Doctors, and very long scarves.

When I first got into Doctor Who, I wanted to let everyone else in my orbit know about it. Because I was seventeen years old, I had to do so in the most dramatic way possible, so I did what any dedicated fan would do: I bought seven different colors of yarn and I knit my own version of The Scarf.

It’s appropriate that the most recognizable symbol of Doctor Who that I could think of wasn’t from the same incarnation of Doctor Who that I was watching at the time. It wasn’t even from the same century. My introduction to the show was David Tennant’s tenure during New Who in the early aughts, but The Scarf was integral to the wardrobe of the fourth incarnation, played by Tom Baker during the Classic Who series in the 1970s. At the time I liked to think that wearing a symbol of the classic show somehow marked me as being a more serious and more dedicated fan than the friends I had who only watched the more recent seasons…even though I preferred the more recent seasons myself. But by repurposing an anachronistic costume piece, I was living out the show’s playful irreverence for and affection toward its own history. I was also following the Doctor’s own costuming choices by using an eccentric wardrobe piece to try to assert a part of my own identity.

Doctor Who is the ultimate time travel show. Its episodic nature and its habit of swapping out the actors who play the titular role grants new viewers freedom to choose wherever they’d like to start watching; in effect, the viewer can choose to time travel throughout the show, dropping into each story in the same way that the Doctor drops in on historical events. The only real constant is the show’s embrace of change.

Doctor Who’s space/time travel conceit allows the show to take place at any place, in any time; its serialized structure allows it to loosely string together unrelated stories into one long romp. (David Tennant’s Ten famously refers to the course of history as a “wibbly-wobbly timey-wimey ball.”) Although some incarnations of the Doctor—like Peter Capaldi’s Twelve and Colin Baker’s Six—skew grim, the show overall maintains an attitude of playfulness. Tom Baker’s Four has a habit of offering candy to everyone he meets, including his adversaries; David Tennant’s Ten engages in frequent wordplay; Peter Davison’s Five wears a stalk of celery on his lapel.

Buy the Book

A Prayer for the Crown-Shy

This playfulness extends to the show’s own timelines and canon. Nothing is truly sacred in Doctor Who; even when the Doctor’s home planet is destroyed in the hiatus between Classic and New Who, it’s eventually brought back through a loophole in time. In the show’s continuity, time is a malleable thing with very few fixed points. The show calls back to previous episodes all the time, even if they’ve been erased from canon. This makes for fertile ground for creative storytelling—the BBC has produced an astounding number of official books and audio dramas, not to mention over fifty years’ worth of TV episodes.

Fans of the show take advantage of that fertile ground as well. It’s possible to write fanfiction set in any time, at any place, with any other characters from any other story, and still have a piece of fanfiction that is distinctly Doctor Who, provided that a certain time-traveling alien pops in. (Archive of Our Own alone currently lists more than 100,000 works under a Doctor Who tag.) Fans have the freedom to drop the Doctor into whatever story they’d like, making the character both ubiquitous and entirely their own.

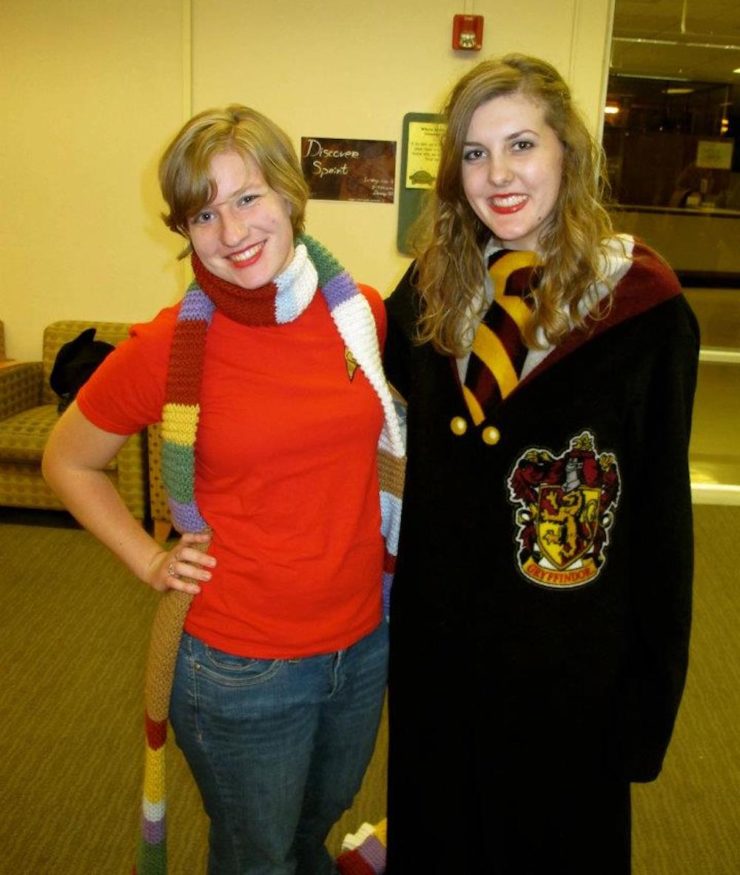

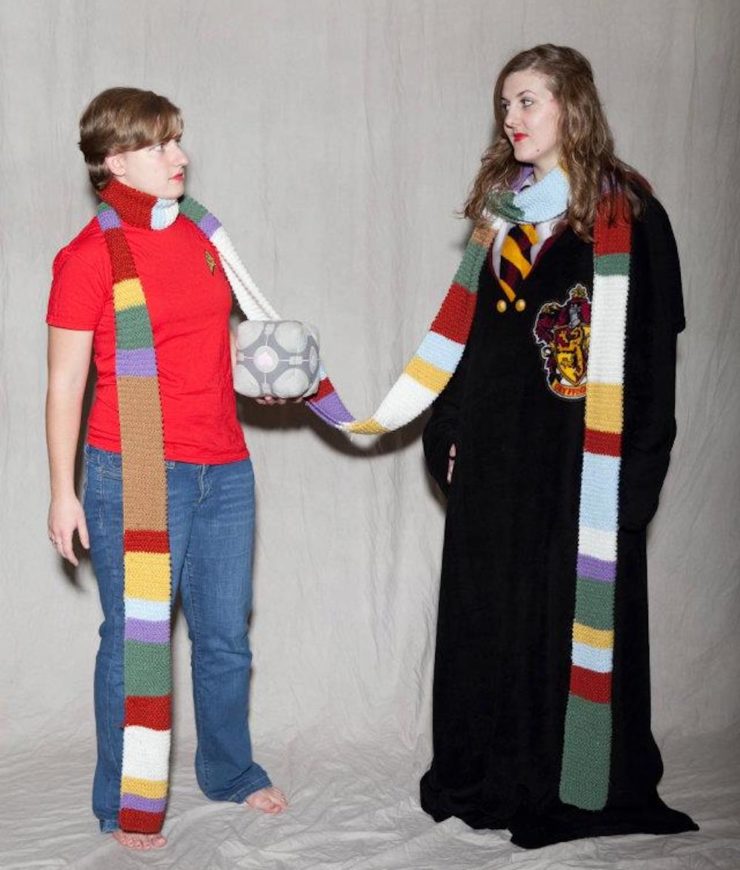

It’s in this spirit of playful creative license that I made my version of The Scarf. There are patterns all over the internet for making screen-faithful copies of The Scarf, but my version is not an exact replica. The stripes are correct—I did follow a pattern—but the colors are all wrong. They’re late-aughts pastels instead of the screen version’s 70s earth tones; I chose them because they were the cheapest soft yarn I could find on a student budget. I was also new to the craft, so I knit my scarf with the slightly-too-loose stitches of an amateur, looping the scarf across my dorm room as I worked. It’s possible that it stretched even longer than the screen version’s canonical fourteen-foot length. I had to roll it up to keep it from taking over my side of the room.

I felt slightly self-conscious about the incorrect colors when I made the scarf, but I wasn’t entering any cosplay competitions, so the mismatch didn’t matter much. None of my friends cared enough about Doctor Who to nitpick the colors. Besides, Tom Baker’s Four didn’t even wear the same scarf all the time; one on-screen variation was all red and purple. My scarf was still recognizable as The Scarf. It was a physical representation of my love for the TV show, something that other fans would acknowledge whenever I wore it out in public. I even had a college professor who wore a more faithful replica of The Scarf that his wife had made him; we’d grin and nod whenever we both wore our scarves to class on the same day. The colors didn’t make my scarf any less a Doctor Who homage; they grounded it as a handmade artifact, unique in its imperfection, something referencing a beloved TV show and also completely my own.

Doctor Who celebrates how it feels to be a physical being, to be alive and inhabit a body. Every time the Doctor regenerates, the character spends an episode or so running around manically in their predecessor’s clothing, trying to save the world in the midst of having their own identity crisis. David Tennant’s Ten, freshly regenerated, pauses mid-speech to comment about how weird his new teeth feel in his mouth. Jodie Whittaker’s Thirteen moves her limbs jerkily, as though she’s unused to piloting her body; Tom Baker’s Four compares getting used to his new body to “settling into a new house .” My own choice to make and wear The Scarf could very well have been a version of my own regeneration; I was in college, building an identity for myself, trying on quirks to see how well they fit. I didn’t wear The Scarf in public for very long; by the time I moved out of the dorms, The Scarf became a decoration, and eventually I lost it.

Newly regenerated versions of the Doctor will complain about the way the previous incarnation’s clothing fits; they don’t feel like themselves until after they’ve saved the world and assembled a new wardrobe that reflects their personalities. Jon Pertwee’s Three and Peter Capaldi’s Twelve both dress like magicians, as befits their slightly aloof personalities; Christopher Eccleston’s Nine wears a leather jacket like armor as a reflection of his PTSD. Each of them chooses how to present their personalities to the world through their clothes.

The show is unapologetically optimistic about human nature, sometimes to a fault. I suppose I was also being overly optimistic when I made my replica of The Scarf. It’s difficult to take anyone wearing a fourteen-foot-long scarf seriously. It’s unwieldy. You have to loop it two or three times to keep from tripping over it, and it will still fall down to your knees. I don’t think I wanted to be taken seriously when I wore it; I wanted to be taken as a serious fan of a TV show that I loved, and that I wanted other people to love. When I stopped wearing it, it was because I wanted to be taken as a serious person in a different sort of way. When I made my version of The Scarf, I was doing the same thing as the characters on the show: I was declaring my allegiance to a humanist time-traveling alien by co-opting part of his costume. I was wearing my heart—and my love for the optimism of the show—quite literally around my shoulders.

Sarah Welch-Larson is interested in feminist theory and theology, sad men in space, and stories about agency and creation, especially when they include cyborgs or androids. She is the co-host of the Seeing & Believing podcast, a staff writer at Bright Wall/Dark Room, and the author of the book Becoming Alien: The Beginning and End of Evil in Science Fiction’s Most Idiosyncratic Franchise. She lives in Chicago with her husband, their dog, and about three dozen houseplants.