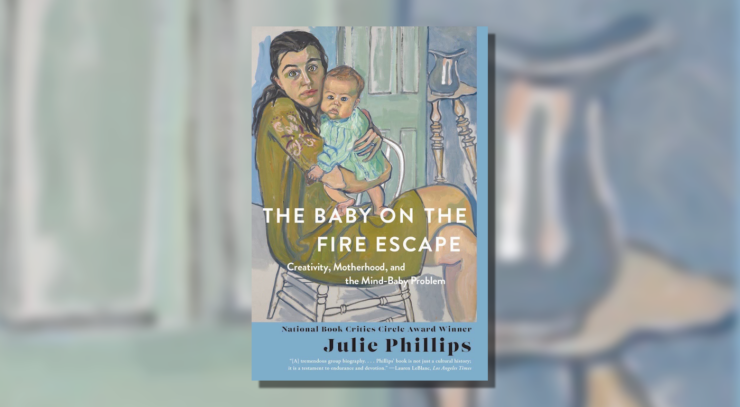

Please enjoy this excerpt from Julie Phillips’ The Baby on the Fire Escape: Creativity, Motherhood, and the Mind-Baby Problem, an insightful, provocative, and witty exploration of the relationship between motherhood and art—for anyone who is a mother, wants to be, or has ever had one, now out in paperback.

What does a great artist who is also a mother look like? What does it mean to create, not in “a room of one’s own,” but in a domestic space? In The Baby on the Fire Escape, award-winning biographer Julie Phillips traverses the shifting terrain where motherhood and creativity converge.

With fierce empathy, Phillips evokes the intimate and varied struggles of brilliant artists and writers of the twentieth century. Ursula K. Le Guin found productive stability in family life, and Audre Lorde’s queer, polyamorous union allowed her to raise children on her own terms. Susan Sontag became a mother at nineteen, Angela Carter at forty-three. These mothers had one child, or five, or seven. They worked in a studio, in the kitchen, in the car, on the bed, at a desk, with a baby carrier beside them. They faced judgement for pursuing their creative work—Doris Lessing was said to have abandoned her children, and Alice Neel’s in-laws falsely claimed that she once, to finish a painting, left her baby on the fire escape of her New York apartment.

As she threads together vivid portraits of these pathbreaking women, Phillips argues that creative motherhood is a question of keeping the baby on that apocryphal fire escape: work and care held in a constantly renegotiated, provisional, productive tension. A meditation on maternal identity and artistic greatness, The Baby on the Fire Escape illuminates some of the most pressing conflicts in contemporary life.

In 1964, a thirty-four-year-old woman and her family move for the year, for her husband’s academic fellowship, to a house in suburban California. Her two daughters are in school but her son is a baby, so her days are not her own. Their subdivision has no sidewalks to push a baby carriage. There are no city buses. She doesn’t drive. Even at home in Portland, Oregon, her mobility is limited to fifteen blocks downhill to Safeway and back up again, about all she can manage with a stroller and a few bags of groceries. It’s hard to go anywhere with a baby, in the days before disposable diapers. On a cross-country drive one summer she and her husband ran out of clean laundry, so they drove across Texas with a wet cloth diaper flapping out the window to dry in the wind, like a white flag of surrender.

Buy the Book

The Baby on the Fire Escape

She is starting to come back to herself after her most recent pregnancy, which she spent in depression and despair. She isn’t unhappy as a mother: she feels more herself in the midst of a family, not less, and hasn’t stopped writing. But she hadn’t wanted a third child and was afraid a new baby would end her writing career, just when she had finally found an audience. The birth made the depression lift a little, and she loves the new baby, but she has the same problem all new parents have: there aren’t enough hours in the day, and it feels like there never will be again.

Every evening, after her husband has put the children to bed in their rented house, she does some work on a new novel, different from the ones she’s written before. By day she suffers from anxiety and “cabin fever,” but at night she follows the quest of a young man exploring a strange new planet. Dreaming up his adventures gives her a lightheartedness that has to do with letting go of high literary ambitions and enjoying herself. A journey across a planet with four moons, on the back of a giant flying cat? That’s one way to get out of the house. The imaginative distance from her daily life frees her up and gives her the “inventive spark” she needs.

Ursula K. Le Guin dealt with mothering and writing by keeping the two in separate spheres of thought. When she was “tied down” in her daily life, she sought her freedom in her imagination. Neel and Lessing used their motherhood as material, but Le Guin approached mothering and writing as two distinct projects that happened to occupy the same place and time. Nourished by the security of a family, she claimed authority by leaving home in her work, writing about male protagonists in invented worlds. Ambitious and proud, she wrote about the deeds of heroes, while she limited motherhood’s claim on her selfhood by becoming, in her fiction, a man.

Where Doris Lessing and Alice Neel ditched the motherhood plot to raise children outside traditional marriages, Le Guin claimed a space of her own within it. For Le Guin, as for Lessing, it was the loss of her maternal self when her children left home that made her want to put the narratives of mother and writer together. But for a long time she didn’t know how to write about her own experience in a genre in which mothers are seldom subjects. She didn’t see how a mother could be a hero.

In September 1953, a graduate student in French literature stands on the deck of the ocean liner Queen Mary. She is there because she has a grant to spend a year in France, and also because she is bored with academic life and wants to get away. Her brother Karl, who has come to see her off, thinks she seems fragile and sad, standing there alone. She has been, but that very night she falls in love.

The man she met was Charles Le Guin, a fellow Fulbright scholar, a handsome historian from Macon, Georgia, who was writing a thesis on the French Revolution. Ursula thought he had a foreign accent. He judged her “awfully snooty and shy.” Once they got over their first misapprehensions, they became inseparable. In Paris they moved into a hotel in the Quartier Latin with two new Fulbright friends: Ursula and her roommate on one floor, Charles and his on another, with shared toilets down the hall. They went together to plays, concerts, museums, enjoying the romance of Paris. In their rooms the four friends played games, dressing up and staging scenes from operas, discovering a shared sense of fantasy. A few weeks after Ursula and Charles arrived, as they were walking back from a concert through the Tuileries, they paused under the arch and Charles proposed.

Deeply in love, Ursula began picturing the family that she and Charles would make together. In a letter from Aix-en-Provence, she wrote him that she had been to visit friends in the country, and watching their small daughter playing with a cat in the garden had “set me to thinking of an autumn afternoon in our garden with a little one and a minou [kitty-cat] and all, and I must say this is a persistent picture in my mind. You have no idea, Charles, how vastly and intensely bourgeoise I am.”

But she also wrote that she’d dreamed she and Charles were flying, supported by books. He was confident; she worried about downdrafts. He was good at steering, while she kept “laughing and losing altitude.” It wasn’t hard to do: “You simply attach a book to the front end of a sort of surf-board, and spread-eagle yourself on it with your feet over the edge, and trot a little, and woop! there you are gliding. The book is for balance.”

One trap for women of Ursula’s generation, if they were not ready to believe in their own ambition, was to pursue vicarious success by marrying high-flying, high-maintenance men. But in Charles Ursula chose a man whose gifts and interests complemented hers, and who would let her do her bookish gliding. From a family of farmers, he had been raised by strong women and didn’t feel a need to look manly. He had a domestic streak and liked raising children and baking cakes. Where Ursula was a worrier and an arguer, he was easygoing and even-tempered. They shared a love of history and literature and a quiet indifference to convention.

Ursula envied her Radcliffe classmate Adrienne Rich her early success, the two acclaimed books of poetry that she published while barely out of college. But Rich had married a Harvard economist and though he helped with their three children, Rich felt in the 1950s that his professional life was “the real work in the family,” while her writing was “a kind of luxury, a peculiarity of mine.” In her marriage to a different kind of man, Ursula was able to maintain her boundaries and claim an equal role. Thinking back to her ambitious Harvard boyfriend, she would come to realize how lucky her escape had been.

As soon as she married Charles, Ursula abandoned her own academic prospects. “I went to the Bibliothèque Nationale with Charles sometimes and fiddled around with Jean Lemaire. I loved handling the old books, and the language and all. But I wasn’t serious. Charles was doing real research and building up his thesis. I had got free.” She read, she learned from Charles about revolution, and she devoted herself to writing poetry and fiction.

In the next few years a novel she submitted got encouraging rejection letters, while Charles and her parents read her work and affirmed her talent. Three years later, in Moscow, Idaho, where it was so cold in winter that the books in Charles’s study froze to the wall, she had her first child, her daughter Elisabeth, and kept on writing.

Excerpted from The Baby on the Fire Escape, copyright © 2022 by Julie Phillips.