Exorcist III is a fascinating, maximalist, baggy film—an existential meditation wrapped up in a psychological thriller, that had a more “horror” element grafted onto it by meddling studio execs. It’s a movie that expects its audience to keep up with weird pop culture references, surrealist imagery, and dodgy cosmology, and apologizes for nothing. And about halfway into its runtime, it has one of the most interesting dream sequences I’ve ever watched.

For background: William Peter Blatty wrote The Exorcist, the novel, based on a real exorcism case that he became obsessed with while he was a student at Georgetown. He updated and changed some of the details, focusing the story on actress Chris McNeil, her daughter Regan, and the tormented priest, Damian Karras, who tries to help them. But there’s another equally important character in the book: Detective Kinderman. He investigates a series of church vandalisms in the area, and when Chris McNeil’s director is murdered, he ends up entangled in the McNeil family drama. He and Karras gradually become friends, bonding particularly over a love of movies.

William Friedkin staged the film more as a domestic drama—he gave plenty of screentime to Karras’ crisis of faith, but much of the film’s power lies in the relationship between Chris and Regan. In Friedkin’s version, Kinderman’s only a small player, and you don’t get the sense of his and Karras’ friendship. What will become a close relationship with Father Dyer only begins in the film’s final scene.

Blatty and Friedkin developed some ideas for a follow-up movie focused on Kinderman, but when that fell apart Blatty wrote the story into the novel Legion. He then worked with a couple of different production companies to turn it back into a movie, met with John Carpenter a bunch to get him to direct, before finally ended up directing it himself… and then the studio came in and made Blatty change the ending, renamed it Exorcist III, and forced him to add an exorcism despite Exorcist II: Heretic being a titanic flop. Given all that, it’s kind of amazing that the movie isn’t a total disaster, but even more surprising: it’s actually a fascinating, thoughtful film that holds up. It has an astonishing performance from Brad Dourif, and one of the greatest jump scares in film history. And, as Alex Bledsoe has written about, the Director’s Cut is pretty fabulous.

Buy the Book

Knock Knock Open Wide

I’m going to talk about one section in particular without spoiling anything, and then dive into a larger theme that will be very spoilery—I’ll warn you, though, no jump scares from me.

At one point in Exorcist III, Kinderman calls the late Father Karras his “best friend”, which is baffling if you’ve only seen the movie, but makes sense if you’ve read the two books. Building on that, Blatty makes the friendship between Kinderman and Father Dyer the heart of the film. Two middle-aged men, dedicated to their work, who desperately need each other but hate to admit it; each, separately, cite the fifteenth anniversary of Karras’ death as an excuse to comfort the other, ducking the fact that they need the comfort just as much. As Kinderman begins investigating a terrifying new case—a series of grisly murders that mimic those of the Gemini Killer, a murderer who was executed fifteen years earlier—he finds his conversations with Dyer getting spikier and spikier. How can Dyer have a belief in a just and orderly universe when children are being murdered in cold blood?

But like the original Exorcist, what makes this movie work is the human, idiosyncratic relationship between these two very different men that balances out the dark philosophy. The movie is also weirdly funny, as when a nurse coming to check on Father Dyer during a hospital stay imitates Gilda Radner’s Emily Littella, and the priest responds by saying “May the Schwartz be with you”—both very specific pop culture references, confusing to people under, say, 50, and the first things that would have been cut by a screenwriter who wanted to make an “accessible” movie. Instead, it’s these moments that set the movie in a specific time, and show us people talking the way people actually talk, with references and jokes that cross in mid-air and sometimes don’t land at all.

This pop culture comfort becomes more important halfway through the movie, when Kinderman has a dream that changes the plot of the film. In most movies a dream sequence would maybe be kind of annoying, but in the world of The Exorcist dreams are important, often even prophetic: in the original, Karras had dreams that tied him to Merrin without knowing it; in the television series, Father Tomas’ dreams lead him to an exorcist named Marcus Keane, who ultimately changes the course of his life.

In Exorcist III I think you can argue that Kinderman’s dream is a vision of heaven—but Kinderman being Kinderman, the vision is mediated through pop culture references.

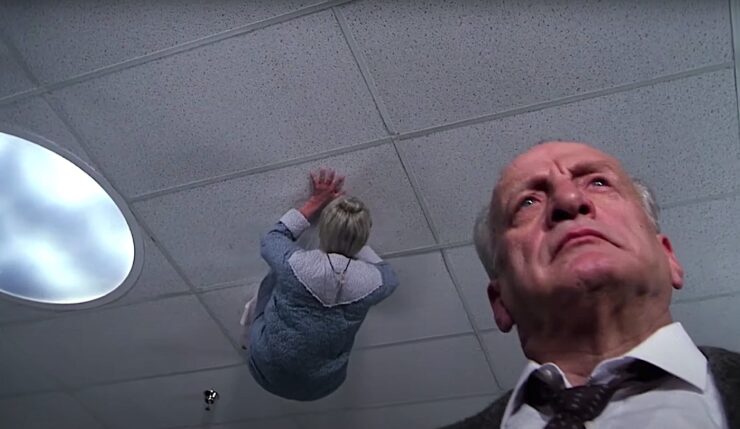

The dream begins with a musical snowglobe falling and shattering—an obvious nod to Citizen Kane, but also a slightly more subtle hat tip to Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes, along with a hint that Kinderman’s daughter will be in danger later. (We already know he’s a Powell-Pressburger fan because he tells his daughter to “watch out for Red Shoes” when she heads to dance class.) Then we’re with Kinderman in a vast train station that is very reminiscent of A Matter of Life and Death—specifically the part of the afterlife we see in the opening of that film, that resembles nothing so much as the waiting room of a cosmic train station, a liminal space where the living and the dead can communicate. In terms of plot, we meet the young boy who was the Gemini Killer’s first victim, the priest who was his second victim, and we see the third victim as well—this is how the audience learns, along with Kinderman, that this character has died. And this along with the hint about the danger his daughter will be in, are what tell us that this dream is “true”.

The people in the station have enormous, feathery, cartoonish white wings, again looking like the wings the newly-dead are given in A Matter of Life and Death, but maybe even more like the wings Clarence works to earn in It’s a Wonderful Life, the movie Dyer and Kinderman just watched together. And even more: a brass band is playing—possibly a reference to the big band-loving protagonist of Here Comes Mr. Jordan, which was advertised as a coming attraction at the theater where Kinderman and Father Dyer went to for their Capra fix—and instead of a heavenly choir Kinderman sees the Lennon Sisters, long a staple of Lawrence Welk’s and Andy Williams’ variety shows.

And then we get to the cameos:

- Samuel L Jackson as a man sitting and listening to a radio (this was just an early film appearance for future Agent Fury, though, not really a celebrity cameo);

- Fabio as a dour angel;

- And best of all, Patrick Ewing as the Angel of Death, slapping tarot cards down on the bed of the recently murdered character—The Hanged Man all the way down.

Earlier in the film there are cameos by C. Everett Koop and Larry King, but in those cases those are meant to be C. Everett Coop and Larry King, two prominent men out for lunch at a Washington DC restaurant. They’re not playing anyone. Here, though, the cameos kind of ask a different question. Are Fabio and Patrick Ewing playing angels? Or is this, again, Kinderman’s mind, translating otherworldly apparitions into pop culture icons he can understand, in a setting that reminds him of three different afterlife-based fantasy classics?

In the context of the world of The Exorcist, however, it means a little bit more. And here is where I’ll have to seriously spoil this movie and its predecessor.

From a certain point of view, The Exorcist has a happy ending—or, at least, a redemptive one. Father Karras has been twisting himself up in knots about his calling. By the time we meet him his faith is on thin ice, and another half hour later he openly admits wanting to quit the priesthood. But in the end, after going through the horrors of the exorcism, he sacrifices himself to save Regan, defeats a demon called Pazuzu, and is able to at least somewhat receive Last Rites. In the world of the film, this is a decent death. In Exorcist II, one plot thread follows a different priest’s investigation into the McNeil exorcism, and specifically whether Lankester Merrin, whom Karras assisted, was a heretic. That movie ends with the confirmation that Merrin was in communion with his church, and with Pazuzu seemingly defeated (again).

Exorcist III then expands to posit that Karras’ soul has not, in fact, been safely spirited off to one afterlife or another, but was rather trapped and tormented inside his mostly catatonic, reanimated corpse, which is being piloted by a tag team of Pazuzu and the soul of the recently executed Gemini Killer.

The movie opens with Dyer’s worry for him, when the other priest includes him in his prayers for the dead as he serves Mass. Then we check in on Kinderman’s loneliness, revisit those iconic Georgetown steps, and see how much these two men still miss their friend. That all makes sense on a purely human, earthly level. Kinderman and Dyer discuss his case, which bears an uncanny resemblance to the Gemini murders. They talk movies and free will. Dyer goes to a hospital for a routine check-up, Kinderman visits him, the men banter, all seems well.

But the dream sequence shifts all that.

The dream sequence tells us, along with Kinderman, that Dyer is the Gemini’s latest victim. This confirms Kinderman’s idea that these new murders are connected to Karras. And indeed, he then learns that of all the hospitals in the world, Dyer checked into the one that had been caring for an unclaimed “Patient X” for fifteen years—Karras’ body, used as a staging ground for the Gemini’s post-death murder spree.

The dream sequence drags the hard-nosed agnostic Kinderman into a different kind of movie. Having received a prophetic dream, he has to enter into Dyer and Karras’ world, allow room for the inexplicable and surreal. The imagery of the dream sequence bleeds more and more into Kinderman’s life until the movie ends with him participating in an exorcism (kind of) and shooting his old friend’s body to free his soul at last. (The paperwork on this case is gonna be a bear.) The dream sequence does all that, and it does it by staying true to Kinderman’s character, and by using the kind of surrealism that short circuits rational thinking and only makes sense if you let yourself trust it. And the movie as a whole is willing to break its own worldbuilding, to ask questions about the ending of the first film, and posit that its universe is far stranger and more unwieldy that we thought. What kind of world does Kinderman live in, if Karras can be tortured like he was? And what does this say about Dyer’s belief in order, if it’s ownly his own grisly murder, and an opaque and unsettling dream, that can finally save Karras and free Georgetown from a revenant murderer?

I love the fact that in the middle of this extremely bumpy franchise, Blatty and his team weren’t afraid to lean into weirdness, to ask giant, knotty questions, and, most of all, to trust their audience to come with them.

Leah Schnelbach wants more movies to trust the audience, and they want the audience to prove them right. Come join them in the liminal train station of Zombie Twitter or Blue Sky or whatever.