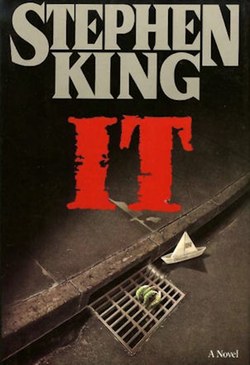

This is the big one, folks. Stephen King’s un-Google-able book, It, took four years to write, and It remains his biggest book weighing in at a hefty four pounds. It’s his most ambitious book, one of his most popular, and, just as The Stand represented a breaking point between Carrie, ‘Salem’s Lot, and The Shining and the next phase of his career, It represents a summary of all that has come before, an attempt to flush out his old interests and move forward.

If The Stand brought an end to the books he wrote before he was famous, then It represents an end of the books he conceived of or wrote in the first flush of his fame, and the beginning of a stage in his career when he had nothing more to prove. Flawed, strange, by turns boring and shocking, It is one of King’s most frustrating and perplexing books. It’s also his saddest.

The first in what turned out to be a perfect storm of new Stephen King novels, It was the first of four new books published in a 14-month period from September 1986 until the end of 1987. It came first in September, then the reading public was pummeled by The Eyes of the Dragon, Misery, and The Tommyknockers in rapid succession. With a first printing of one million copies (priced in hardcover at $22.95, which would be close to $44 in today’s dollars) It went on to be ranked the tenth best-selling novel of the 1980s, pushing 1,115,000 copies by 1990. For King it was his confirmation ceremony, his bar mitzvah, his coming of age.

It was, according to King, “…the summation of everything I have learned and done in my whole life to this point.” It was also a book he dreaded writing. It took four years, and for three of those he let it “percolate” which is a bestselling author’s way of saying “I thought about it a lot while buying expensive motorcycles.” King wrote the first rough draft at the end of 1980, right after Firestarter was published, and if you think It is a tough read it was almost a year before King could write again after that first draft because he felt so drained. The book was so important to him that he even relocated his family for it, moving them to Bangor. He says:

We moved here [Bangor] in 1979…We had been living down in Lovell—we had two choices. There was Portland and there was Bangor. Tabby wanted to go to Portland, and I wanted to go to Bangor because I thought that Bangor was a hard-ass working class town…and I thought that the story, the big story that I wanted to write, was here. I had something fixed in my mind about bringing together all my thoughts on monsters and the children’s tale ‘Three Billy Goats Gruff’ and I didn’t want it to be in Portland because Portland is a kind of yuppie town. There had been a story in the newspaper about the time we decided to move up here about a young man who came out of the Jaguar Tavern during the Bangor Fair. He was gay, and some guys got to joking with him. Then the joking got out of hand, and they threw him over the bridge and killed him. And I thought, that’s what I want to write about, Tabby did not really want to come here, but eventually we did.

As always, the guy who makes the eight-figure advances gets to call the shots. King arrived in Bangor and started roaming around, collecting material:

Before I started writing It…I walked all over town. I asked everybody for stories about places that caught my attention. I knew that a lot of the stories weren’t true but I didn’t care. The ones that really sparked my imagination were the myths. Somebody told me…apparently you can put a canoe down into the sewers just over across from here at the Westgate Mall and you can come out by the Mount Hope cemetery at the other end of town…This same guy told me that the Bangor sewer system was built during the WPA and they lost track of what they were building under there. They had money from the federal government for sewers, so they built like crazy. A lot of the blueprints have now been lost and it’s easy to get lost down there. I decided I wanted to put all that into a book and eventually I did…Bangor became Derry. There is a Bangor in Ireland, located in the county of Derry, so I changed the name of the fictional town to Derry. There is a one-to-one correlation between Bangor and Derry. It’s a place that I keep coming back to, even as recently as the novel Insomnia…Castle Rock is a lot more fictionalized than Derry. Derry is Bangor.

Set simultaneously in 1985 and 1958, It is one of Stephen King’s science fiction books—like Under the Dome, The Tommyknockers, and Dreamcatcher—about an alien lifeform that comes to Earth and doesn’t really get along well with the inhabitants; King is as addicted to his 1950s monster movies as he is addicted to his 1950s rock n’ roll. The creature, known as It, takes on the form of whatever its victims are most afraid of—mummies, werewolves, vampires, clowns—and eats them. It’s been doing this every 27 years but in 1958 its cycle is interrupted when it kills George Denbrough. George’s brother, Bill, belongs to a loose coalition of kids, each with a different problem, who have dubbed themselves The Losers Club. Bill has a stutter, Ben Hascom is fat, Eddie Kaspbrak has an overprotective mother and asthma, Richie Tozier is a loudmouth who’s always defensively doing voices and cracking wise, Mike Hanlon is a nerdy African-American kid, and Beverly Marsh is a girl with an abusive father. Their enemies are a gang of evil greasers, who seem to be refugees from every King book since Carrie (see also: “The Body”, Christine, and “Sometimes They Come Back”). The Losers Club manage to beat It through a combination of self-actualization and physical violence, and then they forget about what happened.

?They grow up, move away from Derry and they all become wildly successful. Then they are reminded of the events of the summer of ‘58 when the murders start again and Mike Hanlon calls them all back home. Losers Club member Stan Uris kills himself right away, and the other adults don’t fare so well either. But go back to Derry they do and while some of them die others pull together and after 1138 pages they manage to defeat It with the assistance of a metaphysical being known as the Turtle. The book leaps back and forth between 1985 to 1958, building up to the final confrontation in both timelines while taking long digressions to dish out the history of Derry and It going all the way back to 1740.

Coming off of Thinner and Christine and the long-in-the-works Pet Sematary, this book feels big, fresh, red, dripping, vital, and raw. Its style is over-the-top right from the beginning. On page two we hear about a guy who drowned in the Derry sewers and King makes sure to mention that his bloated corpse is discovered with his penis eaten off by fish. A few pages later, five-year-old George Denbrough gets his arm torn off at the shoulder. Later, in one of the interludes about Derry’s past, we see someone get their penis nailed to a wall at a lumberjack camp. It’s that kind of book.

It’s also a book that King had a hard time writing. Just as his characters found their memories of childhood erased when they aged into adults, King says that he barely remembers his childhood and there have been some incidents, including seeing his friend run over by a train, that he blocked from his memory and only recovered much later. In writing It, King says that he had to put himself into a semi-dreaming state where he flashed back to his childhood and the more he wrote, the more he remembered.

It was also a book about endings. King’s youngest kid was nine-years-old and he didn’t want to write about traumatized children anymore. Being an ending, King approached It with reluctance. Such reluctance that it isn’t even until page 500 that Pennywise (the iconic evil clown) is mentioned by name and the plot lurches into forward motion. Until this point, it feels like King is spinning his wheels, letting his engine rev, holding back until he has no choice but to dive in and go all the way. He’s abandoned big books at the 500 page mark before (The Cannibals being one notable example) and this time he seems to be trying to build up a ton of backstory, a head of steam, so that he can push forward fast before losing his nerve.

You can make the argument that It is a version of the minotaur story (virgin youth sacrificed to a creature that lives in a labyrinth in exchange for municipal vitality). Or, published in 1986, halfway through Ronald Reagan’s second term, there is a case to be made that It is a response to Reagan’s fetishization of the values of the 1950s. Here are the sleeping adults, awakened by a gay bashing in 1985 who suddenly realize their 1950s childhoods were not some idyllic paradise but a complicated place where racism, bullying, sexism, and terror were all part and parcel of the deal. That the gleaming engine of American enterprise had an ugly underbelly of poverty and suffering. It could be read as a rebuke to the myth of America’s 1950s Norman Rockwell Golden Age, and its mythological power that Reagan liked to haul out as a soothing, hypno-balm at regular intervals.

But ultimately It is about exactly what it says on the box: kids fighting a monster. In an interview, King said, “…my preoccupation with monsters and horror has puzzled me, too. So I put in every monster I could think of and I took every childhood incident I had ever written of before and tried to integrate the two. And It grew and grew and grew…” and became exactly that: a book about monsters and children.

But its kids are a little too perfect, viewed through a soft focus haze that is a bit too luminescent and forgiving. They keep bursting into laughter for no good reason, coming off as slightly unhinged. There’s constant talk about how kids are superior to adults in every way. Adults are cold, they lock the doors when kids cry for help, they are cowardly, they are abusive, out-of-touch, critical, and at best kind of amusing, but not much help at all.

At one point, Bill’s mom muses about her son and one of his friends:

I don’t understand either of them, she thought, Where they go, what they do, what they want…or what will become of them. Sometimes, oh sometimes their eyes are wild, and sometimes I’m afraid for them and sometimes I’m afraid of them…

It’s ridiculously heightened language (“Sometimes, oh sometimes…” really?) and a ridiculously noble idea of childhood. This is what a kid hopes his parents think about him, not what a parent actually thinks about their kids. And it’s this kind of fruity nobility and wish-fulfillment that is the novel’s weakness. At one point Bill delivers a speech in 1958. The 1985 Bill (a famous horror novelist) hears it repeated to him and says, “Those don’t sound like things a real kid would say.” Ben Hanscomb replies, “But we went through a lot.” Bill/Stephen King thinks about it for a minute then says, “Okay. I can buy that.” These aren’t real kids, they’re the kids we all wish we could have been.

In a way, that’s also the strength of the book. Most authors would be embarrassed to write a book about their childhood that casts them as noble heroes fighting a monster that lives under their hometown. King doesn’t know the meaning of the word embarrassed. He sees what a kid wants (to be the hero) and he heads there without any dillydallying, to hell with the critics, to hell with looking dignified, to hell with good taste.

Good taste and Stephen King have never really been on speaking terms, and you get the impression that he agrees with John Waters that “Good taste is the enemy of art.” Nowhere is this more apparent than in the book’s pivotal sex scene. I can’t think of a single scene King has written that has generated as much controversy as the scene where the kids in 1958, aged between 11 and 12 years old, have defeated (for the moment) It but are stumbling around lost in the sewers, unable to find the exit. As a magical ritual, Beverly has sex with each of the boys in turn. She has an orgasm, and afterwards they are able to ground themselves and find their way out of the sewers. Readers have done everything from call King a pedophile to claim it’s sexist, a lapse of good taste, or an unforgiveable breech of trust. But, in a sense, it’s the heart of the book.

It draws a hard border between childhood and adulthood and the people on either side of that fence may as well be two separate species. The passage of that border is usually sex, and losing your virginity is the stamp in your passport that lets you know that you are no longer a child (sexual maturity, in most cultures, occurs around 12 or 13 years old). Beverly is the one in the book who helps her friends go from being magical, simple children to complicated, real adults. If there’s any doubt that this is the heart of the book then check out the title. After all “It” is what we call sex before we have it. “Did you do it? Did he want to do it? Are they doing it?”

Each of the kids in the book doesn’t have to overcome their weakness. Each kid has to learn that their weakness is actually their power. Richie’s voices get him in trouble, but they become a potent weapon that allow him to battle It when Bill falters. Bill’s stutter marks him as an outsider, but the exercises he does for them (“He thrusts his fists against the post, but still insists he sees the ghost.”) become a weapon that weakens It. So does Eddie Kaspbrak’s asthma inhaler. More than once Ben Hanscom uses his weight to get away from the gang of greasers. And Mike Hanlon is a coward and a homebody but he becomes the guardian of Derry, the watchman who stays behind and raises the alarm when the time comes. And Beverly has to have sex (and good sex—the kind that heals, reaffirms, draws people closer together, and produces orgasms) because her weakness is that she’s a woman.

Throughout the book, Beverly’s abusive father berates her, bullies her, and beats her, but he never tries to sexually abuse her until he’s possessed by It. Remember that It becomes what you fear, and while it becomes a Mummy, a Wolfman, and the Creature From the Black Lagoon for the boys, for Beverly It takes the form of a gout of blood that spurts out of the bathroom drain and the threat of her father raping her. Throughout the book, Beverly is not only self-conscious about her changing body, but also unhappy about puberty in general. She wants to fit in with the Losers Club but she’s constantly reminded of the fact that she’s not just one of the boys. From the way the boys look at her to their various complicated crushes she’s constantly reminded that she’s a girl becoming a woman. Every time her gender is mentioned she shuts down, feels isolated, and withdraws. So the fact that having sex, the act of “doing it,” her moment of confronting the heart of this thing that makes her feel so removed, so isolated, so sad turns out to a comforting, beautiful act that bonds her with her friends rather than separates them forever is King’s way of showing us that what we fear most, losing our childhood, turns out not to be so bad after all.

A lot of people feel that the right age for discovering King is adolescence, and It is usually encountered for the first time by teenaged kids. How often is losing your virginity portrayed for girls as something painful, that they regret, or that causes a boy to reject them in fiction? How much does the media represent a teenaged girl’s virginity as something to be protected, stolen, robbed, destroyed, or careful about. In a way, It is a sex positive antidote, a way for King to tell kids that sex, even unplanned sex, even sex that’s kind of weird, even sex where a girl loses her virginity in the sewer, can be powerful and beautiful if the people having it truly respect and like each other. That’s a braver message than some other authors have been willing to deliver.

It’s also a necessary balance. Just one scene before, we encounter the true form of It and the last words in the chapter are, “It was female. And it was pregnant.” The monster of all these children’s nightmares is a reproductive adult female. To follow that up with a more enlightened picture of female sexuality takes some of the curse off of the castration imagery of It itself.

When It came out, King knew that one thing would obsess reviewers: Its length. He even gave an interview saying that long novels were no longer acceptable in America, and he was right. The reviews were, in general, obsessed with Its size. Critics weighed It like a baby (four pounds!), and Twilight Zone Magazine griped that King needed a better editor. The New York Times Book Review wrote, “Where did Stephen King, the most experienced crown prince of darkness, go wrong with It? Almost everywhere. Casting aside discipline, which is as important to a writer as imagination and style, he has piled just about everything he could think of into this book and too much of each thing as well.” Even Publishers Weekly hated how fat this book was: “Overpopulated and under-characterized, bloated by lazy thought-out philosophizing and theologizing, It is all too slowly drowned by King’s unrestrained pen…there is simply too much of It.”

But King was prepared. After all, he was once a fat kid and he knows that there’s nothing people hate more than big boys. King’s weight has made its way into lots of his books, from the sharply observed comforts and curses of food in Thinner, to Vern in “The Body” and “The Revenge of Lard Ass Hogan,” to Ben Hanscom in It, and even Andy McGee’s descent into obesity in Firestarter. King was a fat kid who grew up to write fat books, and he knows that people are going to complain that his book is too damn fat because excess brings out the Puritan in Americans, particularly the critics. But sometimes being fat is part of being beautiful.

While King claims that his book is about childhood, it’s not. His kids are too good, too loyal, too brave. They’re a remembered childhood, not an experienced one. Where It excels is in growing up. The heart of this book is Beverly Marsh losing her virginity and realizing that it’s not such a terrible nightmare after all. This book is about the fact that some doors only open one way, and that while there’s an exit out of childhood named sex, there’s no door leading the other way that turns adults back into children.

It’s in the last chapters of It, after the monster is defeated, that King’s writing really takes off. The book ends not with a battle, not with horror, not with Pennywise, but with Bill trying to connect with his wife who has slipped into a coma. In the last passage in the book he wakes up in bed next to her, touches her, remembers his childhood, but also thinks about how good it is to change, to grow, to be an adult. He remembers that what made childhood so special was that it ended, and this small moment feels like the spark that started this book, the seed from which It grew.

Yes, It is a fat book. But maybe we’re all just jealous. Because to contain so much, it has to be so big. We’re always told it’s what’s on the inside that matters, well maybe being a fat book means it’s got more going on inside where it counts. It’s an amazing book, a flawed book, and sometimes an embarrassing book, but it can’t be summed up in a synopsis or a thesis statement or even in a long, boring article like this. It’s a book that captures something, some slice of time, some intangible feeling about growing up and saying goodbye. As King writes at the end of It “The eye of the day is closing,” and that’s how the forgetting happens. That’s the way your childhood disappears. You close your eyes one minute and when you open them again it’s gone for good. Don’t be scared, It seems to be saying, it’ll all be over in the blink of an eye.

Grady Hendrix is the author of Satan Loves You, Occupy Space, and he’s the co-author of Dirt Candy: A Cookbook, the first graphic novel cookbook. He’s written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today and his story, “Mofongo Knows” appears in the anthology, The Mad Scientist’s Guide to World Domination.