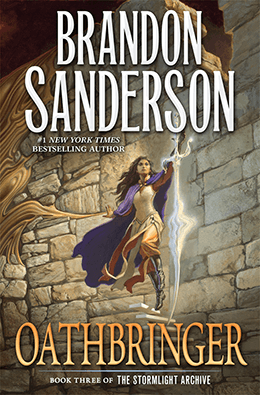

Start reading Oathbringer, the new volume of Brandon Sanderson’s Stormlight Archive epic, right now. For free!

Tor.com is serializing the much-awaited third volume in the Stormlight Archive series every Tuesday until the novel’s November 14, 2017 release date.

Every installment is collected here in the Oathbringer index.

Need a refresher on the Stormlight Archive before beginning Oathbringer? Here’s a summary of what happened in Book 1: The Way of Kings and Book 2: Words of Radiance.

Spoiler warning: Comments will contain spoilers for previous Stormlight books, other works that take place in Sanderson’s cosmere (Elantris, Mistborn, Warbreaker, etc.), and the available chapters of Oathbringer, along with speculation regarding the chapters yet to come.

Chapter 25

The Girl Who Looked Up

I will confess my murders before you. Most painfully, I have killed someone who loved me dearly.

—From Oathbringer, preface

The tower of Urithiru was a skeleton, and these strata beneath Shallan’s fingers were veins that wrapped the bones, dividing and spreading across the entire body. But what did those veins carry? Not blood.

She slid through the corridors on the third level, in the bowels, away from civilization, passing through doorways without doors and rooms without occupants.

Men had locked themselves in with their light, telling themselves that they’d conquered this ancient behemoth. But all they had were outposts in the darkness. Eternal, waiting darkness. These hallways had never seen the sun. Storms that raged through Roshar never touched here. This was a place of eternal stillness, and men could no more conquer it than cremlings could claim to have conquered the boulder they hid beneath.

She defied Dalinar’s orders—the very ones she’d suggested—that all were to travel in pairs. She didn’t worry about that. Her satchel and safepouch were stuffed with new spheres recharged in the highstorm. She felt gluttonous carrying so many, breathing in the Light whenever she wished. She was as safe as a person could be, so long as she had that Light.

She wore Veil’s clothing, but not yet her face. She wasn’t truly exploring, though she did make a mental map. She just wanted to be in this place, sensing it. It could not be comprehended, but perhaps it could be felt.

Jasnah had spent years hunting for this mythical city and the information she’d assumed it would hold. Navani spoke of the ancient technology she was sure this place must contain. So far, she’d been disappointed. She’d cooed over the Oathgates, had been impressed by the system of lifts. That was it. No majestic fabrials from the past, no diagrams explaining lost technology. No books or writings at all. Just dust.

And darkness, Shallan thought, pausing in a circular chamber with corridors splitting out in seven diff rent directions. She had felt the wrongness Mraize spoke of. She’d felt it the moment she’d tried to draw this place. Urithiru was like the impossible geometries of Pattern’s shape. Invisible, yet grating, like a discordant sound.

She picked a direction at random and continued, finding herself in a corridor narrow enough that she could brush both walls with her fingers. The strata had an emerald cast here, an alien color for stone. A hundred shades of wrongness.

She passed several small rooms before entering a much larger chamber. She stepped into it, holding a diamond broam high for light, revealing that she was on a raised portion at the front of a large room with curving walls and rows of stone… benches?

It’s a theater, she thought. And I’ve walked out onto the stage. Yes, she could make out a balcony above. Rooms like this struck her with their humanity. Everything else about this place was so empty and arid. Endless rooms, corridors, and caverns. Floors strewn with only the occasional bit of civilization’s detritus, like rusted hinges or an old boot’s buckle. Decayspren huddled like barnacles on ancient doors.

A theater was more real. More alive, despite the span of the epochs. She stepped into the center and twirled about, letting Veil’s coat flare around her. “I always imagined being up on one of these. When I was a child, becoming a player seemed the grandest job. To get away from home, travel to new places.” To not have to be myself for at least a brief time each day.

Pattern hummed, pushing out from her coat to hover above the stage in three dimensions. “What is it?”

“It’s a stage for concerts or plays.”

“Plays?”

“Oh, you’d like them,” she said. “People in a group each pretend to be someone different, and tell a story together.” She strode down the steps at the side, walking among the benches. “The audience out here watches.”

Pattern hovered in the center of the stage, like a soloist. “Ah…” he said. “A group lie?”

“A wonderful, wonderful lie,” Shallan said, settling onto a bench, Veil’s satchel beside her. “A time when people all imagine together.”

“I wish I could see one,” Pattern said. “I could understand people… mmmm… through the lies they want to be told.”

Shallan closed her eyes, smiling, remembering the last time she’d seen a play at her father’s. A traveling children’s troupe come to entertain her. She’d taken Memories for her collection—but of course, that was now lost at the bottom of the ocean.

“The Girl Who Looked Up,” she whispered.

“What?” Pattern asked.

Shallan opened her eyes and breathed out Stormlight. She hadn’t sketched this particular scene, so she used what she had handy: a drawing she’d done of a young child in the market. Bright and happy, too young to cover her safehand. The girl appeared from the Stormlight and scampered up the steps, then bowed to Pattern.

“There was a girl,” Shallan said. “This was before storms, before memories, and before legends—but there was still a girl. She wore a long scarf to blow in the wind.”

A vibrant red scarf grew around the girl’s neck, twin tails extending far behind her and flapping in a phantom wind. The players had made the scarf hang behind the girl using strings from above. It had seemed so real.

“The girl in the scarf played and danced, as girls do today,” Shallan said, making the child prance around Pattern. “In fact, most things were the same then as they are today. Except for one big difference. The wall.”

Shallan drained an indulgent number of spheres from her satchel, then sprinkled the floor of the stage with grass and vines like from her homeland. Across the back of the stage, a wall grew as Shallan had imagined it. A high, terrible wall stretching toward the moons. Blocking the sky, throwing everything around the girl into shadow.

The girl stepped toward it, looking up, straining to see the top.

“You see, in those days, a wall kept out the storms,” Shallan said. “It had existed for so long, nobody knew how it had been built. That did not bother them. Why wonder when the mountains began or why the sky was high? Like these things were, so the wall was.”

The girl danced in its shadow, and other people sprang up from Shallan’s Light. Each was a person from one of her sketches. Vathah, Gaz, Palona, Sebarial. They worked as farmers or washwomen, doing their duties with heads bowed. Only the girl looked up at that wall, her twin scarf tails streaming behind her.

She approached a man standing behind a small cart of fruit, wearing Kaladin Stormblessed’s face.

“Why is there a wall?” she asked the man selling fruit, speaking with her own voice.

“To keep the bad things out,” he replied.

“What bad things?”

“Very bad things. There is a wall. Do not go beyond it, or you shall die.”

The fruit seller picked up his cart and moved away. And still, the girl looked up at the wall. Pattern hovered beside her and hummed happily to himself.

“Why is there a wall?” she asked the woman suckling her child. The woman had Palona’s face.

“To protect us,” the woman said.

“To protect us from what?”

“Very bad things. There is a wall. Do not go beyond it, or you shall die.”

The woman took her child and left.

The girl climbed a tree, peeking out the top, her scarf streaming behind her. “Why is there a wall?” she called to the boy sleeping lazily in the nook of a branch.

“What wall?” the boy asked.

The girl thrust her finger pointedly toward the wall.

“That’s not a wall,” the boy said, drowsy. Shallan had given him the face of one of the bridgemen, a Herdazian. “That’s just the way the sky is over there.”

“It’s a wall,” the girl said. “A giant wall.”

“It must be there for a purpose,” the boy said. “Yes, it is a wall. Don’t go beyond it, or you’ll probably die.”

“Well,” Shallan continued, speaking from the audience, “these answers did not satisfy the girl who looked up. She reasoned to herself, if the wall kept evil things out, then the space on this side of it should be safe.

“So, one night while the others of the village slept, she sneaked from her home with a bundle of supplies. She walked toward the wall, and indeed the land was safe. But it was also dark. Always in the shadow of that wall. No sunlight, ever, directly reached the people.”

Shallan made the illusion roll, like scenery on a scroll as the players had used. Only far, far more realistic. She had painted the ceiling with light, and looking up, you seemed to be looking only at an infinite sky— dominated by that wall.

This is… this is far more extensive than I’ve done before, she thought, surprised. Creationspren had started to appear around her on the benches, in the form of old latches or doorknobs, rolling about or moving end over end.

Well, Dalinar had told her to practice.…

“The girl traveled far,” Shallan said, looking back toward the stage. “No predators hunted her, and no storms assaulted her. The only wind was the pleasant one that played with her scarf, and the only creatures she saw were the cremlings that clicked at her as she walked.

“At long last, the girl in the scarves stood before the wall. It was truly expansive, running as far as she could see in either direction. And its height! It reached almost to the Tranquiline Halls!”

Shallan stood and walked onto the stage, passing into a different land— an image of fertility, vines, trees, and grass, dominated by that terrible wall. It grew spikes from its front in bristling patches.

I didn’t draw this scene out. At least… not recently.

She’d drawn it as a youth, in detail, putting her imagined fancies down on paper.

“What happened?” Pattern said. “Shallan? I must know what happened.

Did she turn back?”

“Of course she didn’t turn back,” Shallan said. “She climbed. There were outcroppings in the wall, things like these spikes or hunched, ugly statues. She had climbed the highest trees all through her youth. She could do this.”

The girl started climbing. Had her hair been white when she’d started?

Shallan frowned.

Shallan made the base of the wall sink into the stage, so although the girl got higher, she remained chest-height to Shallan and Pattern.

“The climb took days,” Shallan said, hand to her head. “At night, the girl who looked up would tie herself a hammock out of her scarf and sleep there. She picked out her village at one point, remarking on how small it seemed, now that she was high.

“As she neared the top, she finally began to fear what she would find on the other side. Unfortunately, this fear did not stop her. She was young, and questions bothered her more than fear. So it was that she finally struggled to the very top and stood to see the other side. The hidden side…”

Shallan choked up. She remembered sitting at the edge of her seat, listening to this story. As a child, when moments like watching the players had been the only bright spots in life.

Too many memories of her father, and of her mother, who had loved telling her stories. She tried to banish those memories, but they wouldn’t go.

Shallan turned. Her Stormlight… she’d used up almost everything she’d pulled from her satchel. Out in the seats, a crowd of dark figures watched. Eyeless, just shadows, people from her memories. The outline of her father, her mother, her brothers and a dozen others. She couldn’t create them, because she hadn’t drawn them properly. Not since she’d lost her collection…

Next to Shallan, the girl stood triumphantly on the wall’s top, her scarves and white hair streaming out behind her in a sudden wind. Pattern buzzed beside Shallan.

“… and on that side of the wall,” Shallan whispered, “the girl saw steps.”

The back side of the wall was crisscrossed with enormous sets of steps leading down to the ground, so distant.

“What… what does it mean?” Pattern said.

“The girl stared at those steps,” Shallan whispered, remembering, “and suddenly the gruesome statues on her side of the wall made sense. The spears. The way it cast everything into shadow. The wall did indeed hide something evil, something frightening. It was the people, like the girl and her village.”

The illusion started to break down around her. This was too ambitious for her to hold, and it left her strained, exhausted, her head starting to pound. She let the wall fade, claiming its Stormlight. The landscape vanished, then finally the girl herself. Behind, the shadowed figures in the seats started to evaporate. Stormlight streamed back to Shallan, stoking the storm inside.

“That’s how it ended?” Pattern asked.

“No,” Shallan said, Stormlight puffing from her lips. “She goes down, sees a perfect society lit by Stormlight. She steals some and brings it back. The storms come as a punishment, tearing down the wall.”

“Ah…” Pattern said, hovering beside her on the now-dull stage. “So that’s how the storms first began?”

“Of course not,” Shallan said, feeling tired. “It’s a lie, Pattern. A story. It doesn’t mean anything.”

“Then why are you crying?”

She wiped her eyes and turned away from the empty stage. She needed to get back to the markets.

In the seats, the last of the shadowy audience members puffed away. All but one, who stood up and walked out the back doors of the theater. Startled, Shallan felt a sudden shock run through her.

That figure hadn’t been one of her illusions.

She flung herself from the stage—landing hard, Veil’s coat fluttering— and dashed after the figure. She held the rest of her Stormlight, a thrumming, violent tempest. She skidded into the hall outside, glad for sturdy boots and simple trousers.

Something shadowy moved down the corridor. Shallan gave chase, lips drawn to a sneer, letting Stormlight rise from her skin and illuminate her surroundings. As she ran, she pulled a string from her pocket and tied her hair back, becoming Radiant. Radiant would know what to do if she caught this person.

Can a person look that much like a shadow?

“Pattern,” she shouted, thrusting her right hand forward. Luminescent fog formed there, becoming her Shardblade. Light escaped her lips, transforming her more fully into Radiant. Luminescent wisps trailed behind her, and she felt it chasing her. She charged into a small round chamber and skidded to a stop.

A dozen versions of herself, from drawings she’d done recently, split around her and dashed through the room. Shallan in her dress, Veil in her coat. Shallan as a child, Shallan as a youth. Shallan as a soldier, a happy wife, a mother. Leaner here, plumper there. Scarred. Bright with excitement. Bloodied and in pain. They vanished after passing her, collapsing one after another into Stormlight that curled and twisted about itself before vanishing away.

Radiant raised her Shardblade in the stance Adolin had been teaching her, sweat dripping down the sides of her face. The room would have been dark but for the Light curling off her skin and passing through her clothing to rise around her.

Empty. She’d either lost her quarry in the corridors, or it had been a spren and not a person at all.

Or there was nothing there in the first place, a part of her worried. Your mind is not trustworthy these days.

“What was that?” Radiant said. “Did you see it?”

No, Pattern thought to her. I was thinking on the lie.

She walked around the edge of the circular room. The wall was scored by a series of deep slots that ran from floor to ceiling. She could feel air moving through them. What was the purpose of a room like this? Had the people who had designed this place been mad?

Radiant noted faint light coming from several of the slots—and with it the sounds of people in a low, echoing clatter. The Breakaway market? Yes, she was in that region, and while she was on the third level, the market’s cavern was a full four stories high.

She moved to the next slot and peered through it, trying to decide just where it let out. Was this—

Something moved in the slot.

A dark mass wriggled deep inside, squeezing between walls. Like goo, but with bits jutting out. Those were elbows, ribs, fingers splayed along one wall, each knuckle bending backward.

A spren, she thought, trembling. It is some strange kind of spren.

The thing twisted, head deforming in the tiny confines, and looked toward her. She saw eyes reflecting her light, twin spheres set in a mashed head, a distorted human visage.

Radiant pulled back with a sharp gasp, summoning her Shardblade again and holding it wardingly before herself. But what was she going to do? Hack her way through the stone to get to the thing? That would take forever.

Did she even want to reach it?

No. But she had to anyway.

The market, she thought, dismissing her Blade and darting back the way she’d come. It’s heading to the market.

With Stormlight propelling her, Radiant dashed through corridors, barely noticing as she breathed out enough to transform her face into Veil’s. She swerved through a network of twisted passages. This maze, these enigmatic tunnels, were not what she’d expected from the home of the Knights Radiant. Shouldn’t this be a fortress, simple but grand—a beacon of light and strength in the dark times?

Instead it was a puzzle. Veil stumbled out of the back corridors into populated ones, then dashed past a group of children laughing and holding up chips for light and making shadows on the walls.

Another few turns took her out onto the balcony walk around the cavernous Breakaway market, with its bobbing lights and busy pathways. Veil turned left to see slots in the wall here. For ventilation?

The thing had come through one of these, but where had it gone after that? A scream rose, shrill and cold, from the floor of the market below. Cursing to herself, Veil took the steps at a reckless pace. Just like Veil. Running headlong into danger.

She sucked in her breath, and the Stormlight puffing around her pulled in, causing her to stop glowing. After a short dash, she found people gathering between two packed rows of tents. The stalls here sold various goods, many of which looked to be salvage from the more abandoned warcamps. More than a few enterprising merchants—with the tacit approval of their highprinces—had sent expeditions back to gather what they could. With Stormlight flowing and Renarin to help with the Oathgate, those had finally been allowed into Urithiru.

The highprinces had gotten first pick. The rest of their finds were heaped in the tents here, watched over by guards with long cudgels and short tempers.

Veil shoved her way to the front of the crowd, finding a large Horneater man cursing and holding his hand. Rock, she thought, recognizing the bridgeman though he wasn’t in uniform.

His hand was bleeding. Like it was stabbed right through the center, Veil thought.

“What happened here?” she demanded, still holding her Light in to keep it from puffing out and revealing her.

Rock eyed her while his companion—a bridgeman she thought she’d seen before—wrapped his hand. “Who are you to ask me this thing?”

Storms. She was Veil right now, but she didn’t dare expose the ruse, especially not in the open. “I’m on Aladar’s policing force,” she said, digging in her pocket. “I have my commission here…”

“Is fine,” Rock said, sighing, his wariness seeming to evaporate. “I did nothing. Some person pulled knife. I did not see him well—long coat, and a hat. A woman in crowd screamed, drawing my attention. Then, this man, he attacked.”

“Storms. Who is dead?”

“Dead?” The Horneater looked to his companion. “Nobody is dead. Attacker stabbed my hand, then ran. Was assassination attempt, maybe? Person got angry about rule of tower, so he attacked me, for being in Kholin guard?”

Veil felt a chill. Horneater. Tall, burly.

The attacker had chosen a man who looked very similar to the one she had stabbed the other day. In fact, they weren’t far from All’s Alley. Just a few “streets” over in the market.

The two bridgemen turned to leave, and Veil let them go. What more could she learn? The Horneater had been targeted not because of anything he’d done, but because of how he looked. And the attacker had been wearing a coat and hat. Like Veil usually did…

“I thought I’d find you here.”

Veil started, then whirled around, hand going to her belt knife. The speaker was a woman in a brown havah. She had straight Alethi hair, dark brown eyes, bright red painted lips, and sharp black eyebrows almost certainly enhanced with makeup. Veil recognized this woman, who was shorter than she’d seemed while sitting down. She was one of the thieves that Veil had approached at All’s Alley, the one whose eyes had lit up when Shallan had drawn the Ghostblood’s symbol.

“What did he do to you?” the woman asked, nodding toward Rock. “Or do you just have a thing for stabbing Horneaters?”

“This wasn’t me,” Veil said.

“I’m sure.” The woman stepped closer. “I’ve been waiting for you to turn up again.”

“You should stay away, if you value your life.” Veil started off through the market.

The short woman scrambled after her. “My name is Ishnah. I’m an excellent writer. I can take dictations. I have experience moving in the market underground.”

“You want to be my ward?”

“Ward?” The young woman laughed. “What are we, lighteyes? I want to join you.”

The Ghostbloods, of course. “We’re not recruiting.”

“Please.” She took Veil by the arm. “Please. The world is wrong now. Nothing makes sense. But you… your group… you know things. I don’t want to be blind anymore.”

Shallan hesitated. She could understand that desire to do something, rather than just feeling the world tremble and shake. But the Ghostbloods were despicable. This woman would not find what she desired among them. And if she did, then she was not the sort of person that Shallan would want to add to Mraize’s quiver.

“No,” Shallan said. “Do the smart thing and forget about me and my organization.”

She pulled out of the woman’s grip and hurried away through the bustling market.

Chapter 26

Blackthorn Unleashed

TWENTY-NINE YEARS AGO

Incense burned in a brazier as large as a boulder. Dalinar sniffled as Evi threw a handful of tiny papers—each folded and inscribed with a very small glyph—into the brazier. Fragrant smoke washed over him, then whipped in the other direction as winds ripped through the warcamp, carrying windspren like lines of light.

Evi bowed her head before the brazier. She had strange beliefs, his betrothed. Among her people, simple glyphwards weren’t enough for prayers; you needed to burn something more pungent. While she spoke of Jezrien and Kelek, she said their names strangely: Yaysi and Kellai. And she made no mention of the Almighty—instead she spoke of something called the One, a heretical tradition the ardents told him came from Iri.

Dalinar bowed his head for a prayer. Let me be stronger than those who would kill me. Simple and to the point, the kind he figured the Almighty would prefer. He didn’t feel like having Evi write it out.

“The One watch you, near-husband,” Evi murmured. “And soften your temper.” Her accent, to which he was now accustomed, was thicker than her brother’s.

“Soften it? Evi, that’s not the point of battle.”

“You needn’t kill in anger, Dalinar. If you must fight, do it knowing that each death wounds the One. For we are all people in Yaysi’s sight.”

“Yeah, all right,” Dalinar said.

The ardents didn’t seem to mind that he was marrying someone half pagan. “It is wisdom to bring her to Vorin truth,” Jevena—Gavilar’s head ardent—had told him. Similar to how she’d spoken of his conquest. “Your sword will bring strength and glory to the Almighty.”

Idly, he wondered what it would take to actually earn the ardents’ displeasure.

“Be a man and not a beast, Dalinar,” Evi said, then pulled close to him, setting her head on his shoulder and encouraging him to wrap his arms around her.

He did so with a limp gesture. Storms, he could hear the soldiers snicker as they passed by. The Blackthorn, being consoled before battle? Publicly hugging and acting lovey?

Evi turned her head toward him for a kiss, and he presented a chaste one, their lips barely touching. She accepted that, smiling. And she did have a beautiful smile. Life would have been a lot easier for him if Evi would have just been willing to move along with the marriage. But her traditions demanded a long engagement, and her brother kept trying to get new provisions into the contract.

Dalinar stomped away. In his pocket he held another glyphward: one provided by Navani, who obviously worried about the accuracy of Evi’s foreign script. He felt at the smooth paper, and didn’t burn the prayer.

The stone ground beneath his feet was pocked with tiny holes—the pinpricks of hiding grass. As he passed the tents he could see it properly, covering the plain outside, waving in the wind. Tall stuff, almost as high as his waist. He’d never seen grass that tall in Kholin lands.

Across the plain, an impressive force gathered: an army larger than any they’d faced. His heart jumped in anticipation. After two years of political maneuvering, here they were. A real battle with a real army.

Win or lose, this was the fight for the kingdom. The sun was on its way up, and the armies had arrayed themselves north and south, so neither would have it in their eyes.

Dalinar hastened to his armorers’ tent, and emerged a short time later in his Plate. He climbed carefully into the saddle as one of the grooms brought his horse. The large black beast wasn’t fast, but it could carry a man in Shardplate. Dalinar guided the horse past ranks of soldiers—spearmen, archers, lighteyed heavy infantry, even a nice group of fifty cavalrymen under Ilamar, with hooks and ropes for attacking Shardbearers. Anticipationspren waved like banners among them all.

Dalinar still smelled incense when he found his brother, geared up and mounted, patrolling the front lines. Dalinar trotted up beside Gavilar.

“Your young friend didn’t show for the battle,” Gavilar noted.

“Sebarial?” Dalinar said. “He’s not my friend.”

“There’s a hole in the enemy line, still waiting for him,” Gavilar said, pointing. “Reports say he had a problem with his supply lines.”

“Lies. He’s a coward. If he’d arrived, he’d have had to actually pick a side.”

They rode past Tearim, Gavilar’s captain of the guard, who wore Dalinar’s extra Plate for this battle. Technically that still belonged to Evi. Not Toh, but Evi herself, which was strange. What would a woman do with Shardplate?

Give it to a husband, apparently. Tearim saluted. He was capable with Shards, having trained, as did many aspiring lighteyes, with borrowed sets.

“You’ve done well, Dalinar,” Gavilar said as they rode past. “That Plate will serve us today.”

Dalinar made no reply. Even though Evi and her brother had delayed such a painfully long time to even agree to the betrothal, Dalinar had done his duty. He just wished he felt more for the woman. Some passion, some true emotion. He couldn’t laugh without her seeming confused by the conversation. He couldn’t boast without her being disappointed in his bloodlust. She always wanted him to hold her, as if being alone for one storming minute would make her wither and blow away. And…

“Ho!” one of the scouts called from a wooden mobile tower. She pointed, her voice distant. “Ho, there!”

Dalinar turned, expecting an advance attack from the enemy. But no, Kalanor’s army was still deploying. It wasn’t men that had attracted the scout’s attention, but horses. A small herd of them, eleven or twelve in number, galloping across the battlefield. Proud, majestic.

“Ryshadium,” Gavilar whispered. “It’s rare they roam this far east.”

Dalinar swallowed an order to round up the beasts. Ryshadium? Yes… he could see the spren trailing after them in the air. Musicspren, for some reason. Made no storming sense. Well, no use trying to capture the beasts. They couldn’t be held unless they chose a rider.

“I want you to do something for me today, Brother,” Gavilar said. “Highprince Kalanor himself needs to fall. As long as he lives, there will be resistance. If he dies, his line goes with him. His cousin, Loradar Vamah, can seize power.”

“Will Loradar swear to you?”

“I’m certain of it,” Gavilar said.

“Then I’ll find Kalanor,” Dalinar said, “and end this.”

“He won’t join the battle easily, knowing him. But he’s a Shardbearer. And so…”

“So we need to force him to engage.” Gavilar smiled.

“What?” Dalinar said.

“I’m simply pleased to see you talking of tactics.”

“I’m not an idiot,” Dalinar growled. He always paid attention to the tactics of a battle; he simply wasn’t one for endless meetings and jaw wagging.

Though… even those seemed more tolerable these days. Perhaps it was familiarity. Or maybe it was Gavilar’s talk of forging a dynasty. It was the increasingly obvious truth that this campaign—now stretching over many years—was no quick bash and grab.

“Bring me Kalanor, Brother,” Gavilar said. “We need the Blackthorn today.”

“All you need do is unleash him.”

“Ha! As if anyone existed who could leash him in the first place.”

Isn’t that what you’ve been trying to do? Dalinar thought immediately. Marrying me off, talking about how we have to be “civilized” now? Highlighting everything I do wrong as the things we must expunge?

He bit his tongue, and they finished their ride down the lines. They parted with a nod, and Dalinar rode over to join his elites.

“Orders, sir?” asked Rien.

“Stay out of my way,” Dalinar said, lowering his faceplate. The Shardplate helm sealed closed, and a hush fell over the elites. Dalinar summoned Oathbringer, the sword of a fallen king, and waited. The enemy had come to stop Gavilar’s continued pillage of the countryside; they would have to make the first move.

These last few months spent attacking isolated, unprotected towns had made for unfulfilling battles—but had also put Kalanor in a terrible position. If he sat back in his strongholds, he allowed more of his vassals to be destroyed. Already those started to wonder why they paid Kalanor taxes. A handful had preemptively sent messengers to Gavilar saying they would not resist.

The region was on the brink of flipping to the Kholins. And so, Highprince Kalanor had been forced to leave his fortifications to engage here. Dalinar shifted on his horse, waiting, planning. The moment came soon enough; Kalanor’s forces started across the plain in a cautious wave, shields raised toward the sky.

Gavilar’s archers released flights of arrows. Kalanor’s men were well trained; they maintained their formations beneath the deadly hail. Eventually they met Kholin heavy infantry: a block of men so armored that it might as well have been solid stone. At the same time, mobile archer units sprang out to the sides. Lightly armored, they were fast. If the Kholins won this battle—and Dalinar was confident they would—it would be because of the newer battlefield tactics they’d been exploring.

The enemy army found itself flanked—arrows pounding the sides of their assault blocks. Their lines stretched, the infantry trying to reach the archers, but that weakened the central block, which suffered a beating from the heavy infantry. Standard spearman blocks engaged enemy units as much to position them as to do them harm.

This all happened on the scale of the battlefield. Dalinar had to climb off his horse and send for a groom to walk the animal as he waited. Inside, Dalinar fought back the Thrill, which urged him to ride in immediately.

Eventually, he picked a section of Kholin troops who were faring poorly against the enemy block. Good enough. He remounted and kicked his horse into a gallop. This was the right moment. He could feel it. He needed to strike now, when the battle was pivoting between victory and loss, to draw out his enemy.

Grass wriggled and pulled back in a wave before him. Like subjects bowing. This might be the end, his final battle in the conquest of Alethkar. What happened to him after this? Endless feasts with politicians? A brother who refused to look elsewhere for battle?

Dalinar opened himself to the Thrill and drove away such worries. He struck the line of enemy troops like a highstorm hitting a stack of papers. Soldiers scattered before him, shouting. Dalinar laid about with his Shardblade, killing dozens on one side, then the other.

Eyes burned, arms fell limp. Dalinar breathed in the joy of the conquest, the narcotic beauty of destruction. None could stand before him; all were tinder and he the flame. The soldier block should have been able to band together and rush him, but they were too frightened.

And why shouldn’t they be? People spoke of common men bringing down a Shardbearer, but surely that was a fabrication. A conceit intended to make men fight back, to save Shardbearers from having to hunt them down.

He grinned as his horse stumbled trying to cross the bodies piling around it. Dalinar kicked the beast forward, and it leaped—but as it landed, something gave. The creature screamed and collapsed, dumping him.

He sighed, shoving aside the horse and standing. He’d broken its back; Shardplate was not meant for such common beasts.

One group of soldiers tried a counterattack. Brave, but stupid. Dalinar felled them with broad sweeps of his Shardblade. Next, a lighteyed offi er organized his men to come press and try to trap Dalinar, if not with their skill, then their weight of bodies. He spun among them, Plate lending him energy, Blade granting him precision, and the Thrill… the Thrill giving him purpose.

In moments like this, he could see why he had been created. He was wasted listening to men blab. He was wasted doing anything but this: providing the ultimate test of men’s abilities, proving them, demanding their lives at the edge of a sword. He sent them to the Tranquiline Halls primed and ready to fight.

He was not a man. He was judgment.

Enthralled, he cut down foe after foe, sensing a strange rhythm to the fighting, as if the blows of his sword needed to fall to the dictates of some unseen beat. A redness grew at the edges of his vision, eventually covering the landscape like a veil. It seemed to shift and move like the coils of an eel, trembling to the beats of his sword.

He was furious when a calling voice distracted him from the fight. “Dalinar!”

He ignored it.

“Brightlord Dalinar! Blackthorn!”

That voice was like a screeching cremling, playing its song inside his helm. He felled a pair of swordsmen. They’d been lighteyed, but their eyes had burned away, and you could no longer tell.

“Blackthorn!”

Bah! Dalinar spun toward the sound.

A man stood nearby, wearing Kholin blue. Dalinar raised his Shardblade. The man backed away, raising hands with no weapon, still shouting Dalinar’s name.

I know him. He’s… Kadash? One of the captains among his elites. Dalinar lowered his sword and shook his head, trying to get the buzzing sound out of his ears. Only then did he see—really see—what surrounded him.

The dead. Hundreds upon hundreds of them, with shriveled coals for eyes, their armor and weapons sheared but their bodies eerily untouched. Almighty above… how many had he killed? He raised his hand to his helm, turning and looking about him. Timid blades of grass crept up among the bodies, pushing between arms, fingers, beside heads. He’d blanketed the plain so thoroughly with corpses that the grass had a difficult time finding places to rise.

Dalinar grinned in satisfaction, then grew chill. A few of those bodies with burned eyes—three men he could spot—wore blue. His own men, bearing the armband of the elites.

“Brightlord,” Kadash said. “Blackthorn, your task is accomplished!” He pointed toward a troop of horsemen charging across the plain. They carried the silver-on-red flag bearing a glyphpair of two mountains. Left no choice, Highprince Kalanor had committed to the battle. Dalinar had destroyed several companies on his own; only another Shardbearer could stop him.

“Excellent,” Dalinar said. He pulled off his helm and took a cloth from Kadash, using it to wipe his face. A waterskin followed. Dalinar drank the entire thing.

Dalinar tossed away the empty skin, his heart racing, the Thrill thrumming within. “Pull back the elites. Do not engage unless I fall.” Dalinar pulled his helm back on, and felt the comforting tightness as the latches cinched it into place.

“Yes, Brightlord.”

“Gather those of us who… fell,” Dalinar said, waving toward the Kholin dead. “Make certain they, and theirs, are cared for.”

“Of course, sir.”

Dalinar dashed toward the oncoming force, his Shardplate crunching against stones. He felt sad to have to engage a Shardbearer, instead of continuing his fight against the ordinary men. No more laying waste; he now had only one man to kill.

He could vaguely remember a time when facing lesser challenges hadn’t sated him as much as a good fight against someone capable. What had changed?

His run took him toward one of the rock formations on the eastern side of the field—a group of enormous spires, weathered and jagged, like a row of stone stakes. As he entered the shadows, he could hear fighting from the other side. Portions of the armies had broken off and tried to flank each other by rounding the formations.

At their base, Kalanor’s honor guard split, revealing the highprince himself on horseback. His Plate was overlaid with a silver coloring, perhaps steel or silver leaf. Dalinar had ordered his Plate buff d back to its normal slate grey; he’d never understood why people would want to “augment” the natural majesty of Shardplate.

Kalanor’s horse was a tall, majestic animal, brilliant white with a long mane. It carried the Shardbearer with ease. A Ryshadium. Yet Kalanor dismounted. He patted the animal fondly on the neck, then stepped forward to meet Dalinar, Shardblade appearing in his hand.

“Blackthorn,” he called. “I hear you’ve been single-handedly destroying my army.”

“They fight for the Tranquiline Halls now.”

“Would that you had joined to lead them.”

“Someday,” Dalinar said. “When I am too old and weak to fight here, I’ll welcome being sent.”

“Curious, how quickly tyrants grow religious. It must be convenient to tell yourself that your murders belong to the Almighty instead.”

“They’d better not belong to him!” Dalinar said. “I worked hard for those kills, Kalanor. The Almighty can’t have them; he can merely credit them to me when weighing my soul!”

“Then let them weigh you down to Damnation itself.” Kalanor waved back his honor guard, who seemed eager to throw themselves at Dalinar. Alas, the highprince was determined to fight on his own. He swiped with his sword, a long, thin Shardblade with a large crossguard and glyphs down its length. “If I kill you, Blackthorn, what then?”

“Then Sadeas gets a crack at you.”

“No honor on this battlefield, I see.”

“Oh, don’t pretend you are any better,” Dalinar said. “I know what you did to rise to your throne. You can’t pretend to be a peacemaker now.”

“Considering what you did to the peacemakers,” Kalanor said, “I’ll count myself lucky.”

Dalinar leaped forward, falling into Bloodstance—a stance for someone who didn’t care if he got hit. He was younger, more agile than his opponent. He counted on being able to swing faster, harder.

Strangely, Kalanor chose Bloodstance himself. The two clashed, bashing their swords against one other in a pattern that sent them twisting about in a quick shuffle of footings—each trying to hit the same section of Plate repeatedly, to open a hole to flesh.

Dalinar grunted, batting away his opponent’s Shardblade. Kalanor was old, but skilled. He had an uncanny ability to pull back before Dalinar’s strikes, deflecting some of the force of the impact, preventing the metal from breaking.

After furiously exchanging blows for several minutes, both men stepped back, a web of cracks on the left sides of their Plate leaking Stormlight into the air.

“It will happen to you too, Blackthorn,” Kalanor growled. “If you do kill me, someone will rise up and take your kingdom from you. It will never last.”

Dalinar came in for a power swing. One step forward, then a twist all the way about. Kalanor struck him on the right side—a solid hit, but insignificant, as it was on the wrong side. Dalinar, on the other hand, came in with a sweeping stroke that hummed in the air. Kalanor tried to move with the blow, but this one had too much momentum.

The Shardblade connected, destroying the section of Plate in an explosion of molten sparks. Kalanor grunted and stumbled to the side, nearly tripping. He lowered his hand to cover the hole in his armor, which continued to leak Stormlight at the edges. Half the breastplate had shattered.

“You fight like you lead, Kholin,” he growled. “Reckless.”

Dalinar ignored the taunt and charged instead.

Kalanor ran away, plowing through his honor guard in his haste, shoving some aside and sending them tumbling, bones breaking.

Dalinar almost caught him, but Kalanor reached the edge of the large rock formation. He dropped his Blade—it puff d away to mist—and sprang, grabbing hold of an outcropping. He started to climb.

He reached the base of the natural tower moments later. Boulders littered the ground nearby; in the mysterious way of the storms, this had probably been a hillside until recently. The highstorm had ripped most of it away, leaving this unlikely formation poking into the air. It would probably soon get blown down.

Dalinar dropped his Blade and leapt, snagging an outcropping, his fingers grinding on stone. He dangled before getting a footing, then proceeded to climb up the steep wall after Kalanor. The other Shardbearer tried to kick rocks down, but they bounced off Dalinar harmlessly.

By the time Dalinar caught up, they had climbed some fifty feet. Down below, soldiers gathered and stared, pointing.

Dalinar reached for his opponent’s leg, but Kalanor yanked it out of the way and then—still hanging from the stones—summoned his Blade and began swiping down. After getting battered on the helm a few times, Dalinar growled and let himself slide down out of the way.

Kalanor gouged a few chunks from the wall to send them clattering at Dalinar, then dismissed his Blade and continued upward.

Dalinar followed more carefully, climbing along a parallel route to the side. He eventually reached the top and peeked over the edge. The summit of the formation was some flat-topped, broken peaks that didn’t look terribly sturdy. Kalanor sat on one of them, Blade across one leg, his other foot dangling.

Dalinar climbed up a safe distance from his enemy, then summoned Oathbringer. Storms. There was barely enough room up here to stand. Wind buffeted him, a windspren zipping around to one side.

“Nice view,” Kalanor said. Though the forces had started out with equal numbers, below them were far more fallen men in silver and red strewn across the grassland than there were men in blue. “I wonder how many kings get such prime seating to watch their own downfall.”

“You were never a king,” Dalinar said.

Kalanor stood and lifted his Blade, extending it in one hand, point toward Dalinar’s chest. “That, Kholin, is all tied up in bearing and assumption. Shall we?”

Clever, bringing me up here, Dalinar thought. Dalinar had the obvious edge in a fair duel—and so Kalanor brought random chance into the fight. Winds, unsteady footing, a plunge that would kill even a Shardbearer.

At the very least, this would be a novel challenge. Dalinar stepped forward carefully. Kalanor changed to Windstance, a more flowing, sweeping style of fighting. Dalinar chose Stonestance for the solid footing and straightforward power.

They traded blows, shuffling back and forth along the line of small peaks. Each step scraped chips off the stones, sending them tumbling down. Kalanor obviously wanted to draw out this fight, to maximize the time for Dalinar to slip.

Dalinar tested back and forth, letting Kalanor fall into a rhythm, then broke it to strike with everything he had, battering down in overhand blows. Each fanned something burning inside of Dalinar, a thirst that his earlier rampage hadn’t sated. The Thrill wanted more.

Dalinar scored a series of hits on Kalanor’s helm, backing him up to the edge, one step away from a fall. The last blow destroyed the helm entirely, exposing an aged face, clean-shaven, mostly bald.

Kalanor growled, teeth clenched, and struck back at Dalinar with unexpected ferocity. Dalinar met it Blade with Blade, then stepped forward to turn it into a shoving match—their weapons locked, neither with room to maneuver.

Dalinar met his enemy’s gaze. In those light grey eyes, he saw something. Excitement, energy. A familiar bloodlust.

Kalanor felt the Thrill too.

Dalinar had heard others speak of it, this euphoria of the contest. The secret Alethi edge. But seeing it right there, in the eyes of a man trying to kill him, made Dalinar furious. He should not have to share such an intimate feeling with this man.

He grunted and—in a surge of strength—tossed Kalanor back. The man stumbled, then slipped. He instantly dropped his Shardblade and, in a frantic motion, managed to grab the rock lip as he fell.

Helmless, Kalanor dangled. The sense of the Thrill in his eyes faded to panic. “Mercy,” he whispered.

“This is a mercy,” Dalinar said, then struck him straight through the face with his Shardblade.

Kalanor’s eyes burned from grey to black as he dropped off the spire, trailing twin lines of black smoke. The corpse scraped rock before hitting far below, on the far side of the rock formation, away from the main army.

Dalinar breathed out, then sank down, wrung out. Shadows stretched long across the land as the sun met the horizon. It had been a fine fight. He’d accomplished what he’d wanted. He’d conquered all who stood before him.

And yet he felt empty. A voice within him kept saying, “That’s it? Weren’t we promised more?”

Down below, a group in Kalanor’s colors made for the fallen body. The honor guard had seen where their brightlord had fallen? Dalinar felt a spike of outrage. That was his kill, his victory. He’d won those Shards!

He scrambled down in a reckless half-climb. The descent was a blur; he was seeing red by the time he hit the ground. One soldier had the Blade; others were arguing over the Plate, which was broken and mangled.

Dalinar attacked, killing six in moments, including the one with the Blade. Two others managed to run, but they were slower than he was. Dalinar caught one by the shoulder, whipping him around and smashing him down into the stones. He killed the last with a sweep of Oathbringer.

More. Where were more? Dalinar saw no men in red. Only some in blue—a beleaguered set of soldiers who flew no flag. In their center, however, walked a man in Shardplate. Gavilar rested here from the battle, in a place behind the lines, to take stock.

The hunger inside of Dalinar grew. The Thrill came upon him in a rush, overwhelming. Shouldn’t the strongest rule? Why should he sit back so often, listening to men chat instead of war?

There. There was the man who held what he wanted. A throne… a throne and more. The woman Dalinar should have been able to claim. A love he’d been forced to abandon, for what reason?

No, his fighting today was not done. This was not all!

He started toward the group, his mind fuzzy, his insides feeling a deep ache. Passionspren—like tiny crystalline flakes—dropped around him.

Shouldn’t he have passion?

Shouldn’t he be rewarded for all he had accomplished?

Gavilar was weak. He intended to give up his momentum and rest upon what Dalinar had won for him. Well, there was one way to make certain the war continued. One way to keep the Thrill alive.

One way for Dalinar to get everything he deserved.

He was running. Some of the men in Gavilar’s group raised hands in welcome. Weak. No weapons presented against him! He could slaughter them all before they knew what had happened. They deserved it! Dalinar deserved to—

Gavilar turned toward him, pulling free his helm and smiling an open, honest grin.

Dalinar pulled up, stopping with a lurch. He stared at Gavilar, his brother.

Oh, Stormfather, Dalinar thought. What am I doing?

He let the Blade slip from his fingers and vanish. Gavilar strode up, unable to read Dalinar’s horrified expression behind his helm. As a blessing, no shamespren appeared, though he should have earned a legion of them in that moment.

“Brother!” Gavilar said. “Have you seen? The day is won! Highprince Ruthar brought down Gallam, winning Shards for his son. Talanor took a Blade, and I hear you finally drew out Kalanor. Please tell me he didn’t escape you.”

“He…” Dalinar licked his lips, breathing in and out. “He is dead.” Dalinar pointed toward the fallen form, visible only as a bit of silvery metal shining amid the shadows of the rubble.

“Dalinar, you wonderful, terrible man!” Gavilar turned toward his soldiers. “Hail the Blackthorn, men. Hail him!” Gloryspren burst around Gavilar, golden orbs that rotated around his head like a crown.

Dalinar blinked amid their cheering, and suddenly felt a shame so deep he wanted to crumple up. This time, a single spren—like a falling petal from a blossom—drifted down around him.

He had to do something. “Blade and Plate,” Dalinar said to Gavilar urgently. “I won them both, but I give them to you. A gift. For your children.”

“Ha!” Gavilar said. “Jasnah? What would she do with Shards? No, no. You—”

“Keep them,” Dalinar pled, grabbing his brother by the arm. “Please.”

“Very well, if you insist,” Gavilar said. “I suppose you do already have Plate to give your heir.”

“If I have one.”

“You will!” Gavilar said, sending some men to recover Kalanor’s Blade and Plate. “Ha! Toh will have to agree, finally, that we can protect his line. I suspect the wedding will happen within the month!”

As would, likely, the official re-coronation where—for the first time in centuries—all ten highprinces of Alethkar would bow before a single king.

Dalinar sat down on a stone, pulling free his helm and accepting water from a young messenger woman. Never again, he swore to himself. I give way for Gavilar in all things. Let him have the throne, let him have love.

I must never be king.

Chapter 27

Playing Pretend

I will confess my heresy. I do not back down from the things I have said, regardless of what the ardents demand.

—From Oathbringer, preface

The sounds of arguing politicians drifted to Shallan’s ears as she sketched. She sat on a stone seat at the back of the large meeting room near the top of the tower. She’d brought a pillow to sit on, and Pattern buzzed happily on the little pedestal.

She sat with her feet up, thighs supporting her drawing pad, stockinged toes curling over the rim of the bench in front of her. Not the most dignified of positions; Radiant would be mortified. At the front of the auditorium, Dalinar stood before the glowing map that Shallan and he—somehow combining their powers—could create. He’d invited Taravangian, the highprinces, their wives, and their head scribes. Elhokar had come with Kalami, who was scribing for him lately.

Renarin stood beside his father in his Bridge Four uniform, looking uncomfortable—so basically, same as usual. Adolin lounged nearby, arms folded, occasionally whispering a joke toward one of the men of Bridge Four.

Radiant should be down there, engaging in this important discussion about the future of the world. Instead, Shallan drew. The light was just so good up here, with these broad glass windows. She was tired of feeling trapped in the dark hallways of the lower levels, always feeling that something was watching her.

She finished her sketch, then tipped it toward Pattern, holding the sketchbook with her sleeved safehand. He rippled up from his post to inspect her drawing: the slot obstructed by a mashed-up figure with bulging, inhuman eyes.

“Mmmm,” Pattern said. “Yes, that is correct.”

“It has to be some kind of spren, right?”

“I feel I should know,” Pattern said. “This… this is a thing from long ago. Long, long ago…”

Shallan shivered. “Why is it here?”

“I cannot say,” Pattern replied. “It is not a thing of us. It is of him.”

“An ancient spren of Odium. Delightful.” Shallan flipped the page over the top of her sketchbook and started on another drawing.

The others spoke further of their coalition, Thaylenah and Azir recurring as the most important countries to convince, now that Iri had made it completely clear they had joined the enemy.

“Brightness Kalami,” Dalinar was saying. “The last report. It listed a large gathering of the enemy in Marat, was it?”

“Yes, Brightlord,” the scribe said from her position at the reading desk. “Southern Marat. You hypothesized it was the low population of the region that induced the Voidbringers to gather there.”

“The Iriali have taken the chance to strike eastward, as they’ve always wanted to,” Dalinar said. “They’ll seize Rira and Babatharnam. Meanwhile, areas like Triax—around the southern half of central Roshar—continue to go dark.”

Brightness Kalami nodded, and Shallan tapped her lips with her drawing pencil. The question raised an implication. How could cities go completely dark? These days major cities—particularly ports—would have hundreds of spanreeds in operation. Every lighteyes or merchant wanting to watch prices or keep in contact with distant estates would have one.

Those in Kholinar had started working as soon as the highstorms returned—and then they’d been cut off one by one. Their last reports claimed that armies were gathering near the city. Then… nothing. The enemy seemed to be able to locate spanreeds somehow.

At least they’d finally gotten word from Kaladin. A single glyph for time, implying they should be patient. He’d been unable to get to a town to find a woman to scribe for him, and just wanted them to know he was safe. Assuming someone else hadn’t gotten the spanreed, and faked the glyph to put them off.

“The enemy is making a play for the Oathgates,” Dalinar decided. “All of their motions, save for the gathering in Marat, indicate this. My instincts say that army is planning to strike back at Azir, or even to cross and try to assault Jah Keved.”

“I trust Dalinar’s assessment,” Highprince Aladar added. “If he believes this course to be likely, we should listen.”

“Bah,” said Highprince Ruthar. The oily man leaned against the wall across from the others, barely paying attention. “Who cares what you say, Aladar? It’s amazing you can even see, considering the place you’ve gone and stuck your head these days.”

Aladar spun and thrust his hand to the side in a summoning posture. Dalinar stopped him, as Ruthar must have known that he would. Shallan shook her head, letting herself instead be drawn farther into her sketching. A few creationspren appeared at the top of her drawing pad, one a tiny shoe, the other a pencil like the one she used.

Her sketch was of Highprince Sadeas, drawn without a specific Memory. She’d never wanted to add him to her collection. She finished the quick sketch, then flipped to a sketch of Brightlord Perel, the other man they’d found dead in the hallways of Urithiru. She’d tried to re-create his face without wounds.

She flipped back and forth between the two. They do look similar, Shallan decided. Same bulbous features. Similar build. Her next two pages were pictures of the two Horneaters. Those two looked roughly similar as well. And the two murdered women? Why would the man who strangled his wife confess to that murder, but then swear he hadn’t killed the second woman? One was already enough to get you executed.

That spren is mimicking the violence, she thought. Killing or wounding in the same way as attacks from previous days. A kind of… impersonation?

Pattern hummed softly, drawing her attention. Shallan looked up to see someone strolling in her direction: a middle-aged woman with short black hair cut almost to the scalp. She wore a long skirt and a buttoning shirt with a vest. Thaylen merchant clothing.

“What is that you’re sketching, Brightness?” the woman asked in Veden.

Hearing her own language so suddenly was strange to Shallan, and her mind took a moment to sort through the words. “People,” Shallan said, closing her drawing pad. “I enjoy figure drawing. You’re the one who came with Taravangian. His Surgebinder.”

“Malata,” she said. “Though I am not his. I came to him for convenience, as Spark suggested we might look to Urithiru, now that it has been rediscovered.” She surveyed the large auditorium. Shallan could see no sign of her spren. “Do you suppose we really filled this entire chamber?”

“Ten orders,” Shallan said, “with hundreds of people in most. Yes, I’d assume we could fill it—in fact, I doubt everyone belonging to the orders could fit in here.”

“And now there are four of us,” she said idly, eyeing Renarin, who stood stiff beside his father, sweating beneath the scrutiny as people occasionally glanced at him.

“Five,” Shallan said. “There’s a flying bridgeman out there somewhere— and those are only the ones of us gathered here. There are bound to be others like you, who are still looking for a way to reach us.”

“If they want to,” Malata said. “Things don’t have to be the way they were. Why should they? It didn’t work out so well last time for the Radiants, did it?”

“Maybe,” Shallan said. “But maybe this isn’t the time to experiment either. The Desolation has started again. We could do worse than rely upon the past to survive this.”

“Curious,” the woman said, “that we have only the word of a few stuffy Alethi about this entire ‘Desolation’ business, eh sister?”

Shallan blinked at the casual way it was said, along with a wink. Malata smiled and sauntered back toward the front of the room.

“Well,” Shallan whispered, “she’s annoying.”

“Mmm…” Pattern said. “It will be worse when she starts destroying things.”

“Destroying?”

“Dustbringer,” Pattern said. “Her spren… mmm… they like to break what is around them. They want to know what is inside.”

“Pleasant,” Shallan said, as she flipped back through her drawings. The thing in the crack. The dead men. This should be enough to present to Dalinar and Adolin, which she planned to do today, now that she had her sketches done.

And after that?

I need to catch it, she thought. I watch the market. Eventually someone will be hurt. And a few days later, this thing will try to copy that attack.

Perhaps she could patrol the unexplored parts of the tower? Look for it, instead of waiting for it to attack?

The dark corridors. Each tunnel like a drawing’s impossible line…

The room had grown quiet. Shallan shook out of her reverie and looked up to see what was happening: Ialai Sadeas had arrived at the meeting, carried in a palanquin. She was accompanied by a familiar figure: Meridas Amaram was a tall man, tan eyed, with a square face and solid figure. He was also a murderer, a thief, and a traitor. He had been caught trying to steal a Shardblade—proof that what Captain Kaladin said about him was true.

Shallan gritted her teeth, but found her anger… cool. Not gone. No, she would not forgive this man for killing Helaran. But the uncomfortable truth was that she didn’t know why, or how, her brother had fallen to Amaram. She could almost hear Jasnah whispering to her: Don’t judge without more details.

Below, Adolin had risen and stepped toward Amaram, right into the center of the illusory map, breaking its surface, causing waves of glowing Stormlight to ripple across it. He stared murder at Amaram, though Dalinar rested his hand on his son’s shoulder, holding him back.

“Brightness Sadeas,” Dalinar said. “I am glad you have agreed to join the meeting. We could use your wisdom in our planning.”

“I’m not here for your plans, Dalinar,” Ialai said. “I’m here because it was a convenient place to find you all together. I’ve been in conference with my advisors back at our estates, and the consensus is that the heir, my nephew, is too young. This is no time for House Sadeas to be without leadership, so I’ve made a decision.”

“Ialai,” Dalinar said, stepping into the illusion beside his son. “Let’s talk about this. Please. I have an idea that, though untraditional, might—”

“Tradition is our ally, Dalinar,” Ialai said. “I don’t think you’ve ever understood that as you should. Highmarshal Amaram is our house’s most decorated and well-regarded general. He is beloved of our soldiers, and known the world over. I name him regent and heir to the house title. He is, for all intents, Highprince Sadeas now. I would ask the king to ratify this.”

Shallan’s breath caught. King Elhokar looked up from his seat, where he—seemingly—had been lost in thought. “Is this legal?”

“Yes,” Navani said, arms folded.

“Dalinar,” Amaram said, stepping down several of the steps toward the rest of them at the bottom of the auditorium. His voice gave Shallan chills. That refined diction, that perfect face, that crisp uniform… this man was what every soldier aspired to be.

I’m not the only one who is good at playing pretend, she thought.

“I hope,” Amaram continued, “our recent… friction will not prevent us from working together for the needs of Alethkar. I have spoken to Brightness Ialai, and I think I have persuaded her that our differences are secondary to the greater good of Roshar.”

“The greater good,” Dalinar said. “You think you are one to speak about what is good?”

“Everything I’ve done is for the greater good, Dalinar,” Amaram said, his voice strained. “Everything. Please. I know you intend to pursue legal action against me. I will stand at trial, but let us postpone that until after Roshar has been saved.”

Dalinar regarded Amaram for an extended, tense moment. Then he finally looked to his nephew and nodded in a curt gesture.

“The throne acknowledges your act of regency, Brightness,” Elhokar said to Ialai. “My mother will wish a formal writ, sealed and witnessed.”

“Already done,” Ialai said.

Dalinar met the eyes of Amaram across the floating map. “Highprince,” Dalinar finally said.

“Highprince,” Amaram said back, tipping his head.

“Bastard,” Adolin said.

Dalinar winced visibly, then pointed toward the exit. “Perhaps, son, you should take a moment to yourself.”

“Yeah. Sure.” Adolin pulled out of his father’s grip, stalking toward the exit.

Shallan thought only a moment, then grabbed her shoes and drawing pad and hurried after him. She caught up to Adolin in the hallway outside, near where the palanquins for the women were parked, and took his arm.

“Hey,” she said softly.

He glanced at her, and his expression softened.

“You want to talk?” Shallan asked. “You seem angrier about him than you were before.”

“No,” Adolin muttered, “I’m just annoyed. We’re finally rid of Sadeas, and now that takes his place?” He shook his head. “When I was young, I used to look up to him. I started getting suspicious when I was older, but I guess part of me still wanted him to be like they said. A man above all the pettiness and the politics. A true soldier.”

Shallan wasn’t certain what she thought of the idea of a “true soldier” being the type who didn’t care about politics. Shouldn’t the why of what a man was doing be important to him?

Soldiers didn’t talk that way. There was some ideal she couldn’t quite grasp, a kind of cult of obedience—of caring only about the battlefield and the challenge it presented.

They walked onto the lift, and Adolin fished out a free gemstone—a little diamond not surrounded by a sphere—and placed it into a slot along the railing. Stormlight began to drain from the stone, and the balcony shook, then slowly began to descend. Removing the gem would tell the lift to stop at the next floor. A simple lever, pushed one way or the other, would determine whether the lift crawled upward or downward.

They descended past the top tier, and Adolin took up position by the railing, looking out over the central shaft with the window all along one side. They were starting to call it the atrium—though it was an atrium that ran up dozens upon dozens of floors.

“Kaladin’s not going to like this,” Adolin said. “Amaram as a highprince? The two of us spent weeks in jail because of the things that man did.”

“I think Amaram killed my brother.”

Adolin wheeled around to stare at her. “What?”

“Amaram has a Shardblade,” Shallan said. “I saw it previously in the hands of my brother, Helaran. He was older than I am, and left Jah Keved years ago. From what I can gather, he and Amaram fought at some point, and Amaram killed him—taking the Blade.”

“Shallan… that Blade. You know where Amaram got that, right?” “On the battlefield?”

“From Kaladin.” Adolin raised his hand to his head. “The bridgeboy insisted that he’d saved Amaram’s life by killing a Shardbearer. Amaram then killed Kaladin’s squad and took the Shards for himself. That’s basically the entire reason the two hate each other.”

Shallan’s throat grew tight. “Oh.”

Tuck it away. Don’t think about it.

“Shallan,” Adolin said, stepping toward her. “Why would your brother try to kill Amaram? Did he maybe know the highlord was corrupt? Storms! Kaladin didn’t know any of that. Poor bridgeboy. Everyone would have been better off if he’d just let Amaram die.”

Don’t confront it. Don’t think about it.

“Yeah,” she said. “Huh.”

“But how did your brother know?” Adolin said, pacing across the balcony. “Did he say anything?”

“We didn’t talk much,” Shallan said, numb. “He left when I was young. I didn’t know him well.”

Anything to get off this topic. For this was something she could still tuck away in the back of her brain. She did not want to think about Kaladin and Helaran.…

It was a long, quiet ride to the bottom floors of the tower. Adolin wanted to go visit his father’s horse again, but she wasn’t interested in standing around smelling horse dung. She got off on the second level to make her way toward her rooms.

Secrets. There are more important things in this world, Helaran had said to her father. More important even than you and your crimes.

Mraize knew something about this. He was withholding the secrets from her like sweets to entice a child to obedience. But all he wanted her to do was investigate the oddities in Urithiru. That was a good thing, wasn’t it? She’d have done it anyway.

Shallan meandered through the hallways, following a path where Sebarial’s workers had affixed some sphere lanterns to hooks on the walls. Locked up and filled with only the cheapest diamond spheres, they shouldn’t be worth the effort to break into, but the light they gave was also rather dim.

She should have stayed above; her absence must have destroyed the illusion of the map. She felt bad about that. Was there a way she could learn to leave her illusions behind her? They’d need Stormlight to keep going.…

In any case, Shallan had needed to leave the meeting. The secrets this city hid were too engaging to ignore. She stopped in the hallway and dug out her sketchbook, flipping through pages, looking at the faces of the dead men.

Absently turning a page, she came across a sketch she didn’t recall making. A series of twisting, maddening lines, scribbled and unconnected.

She felt cold. “When did I draw this?”

Pattern moved up her dress, stopping under her neck. He hummed, an uncomfortable sound. “I do not remember.”

She flipped to the next page. Here she’d drawn a rush of lines sweeping out from a central point, confused and chaotic, transforming to the heads of horses with the flesh ripping off, their eyes wide, equine mouths screaming. It was grotesque, nauseating.

Oh Stormfather…

Her fingers trembled as she turned to the next page. She’d scribbled it entirely black, using a circular motion, spiraling toward the center point. A deep void, an endless corridor, something terrible and unknowable at the end.

She snapped the sketchbook shut. “What is happening to me?”

Pattern hummed in confusion. “Do we… run?”

“Where.”

“Away. Out of this place. Mmmmm.”

“No.”

She trembled, part of her terrified, but she couldn’t abandon those secrets. She had to have them, hold them, make them hers. She turned sharply in the corridor, taking a path away from her room. A short time later, she strode into the barracks where Sebarial housed his soldiers. There were plentiful spaces like this in the tower: vast networks of rooms with built-in stone bunks in the walls. Urithiru had been a military base; that much was evident from its ability to efficiently house tens of thousands of soldiers on the lower levels alone.

In the common room of the barracks, men lounged with coats off, playing with cards or knives. Her passing caused a stir as men gaped, then leaped to their feet, debating between buttoning their coats and saluting. Whispers of “Radiant” chased her as she walked into a corridor lined with rooms, where the individual platoons bunked. She counted off doorways marked by archaic Alethi numbers etched into the stone, then entered a specific one.

She burst in on Vathah and his team, who sat inside playing cards by the light of a few spheres. Poor Gaz sat on the chamber pot in a corner privy, and he yelped, pulling closed the cloth on the doorway.

Guess I should have anticipated that, Shallan thought, covering her blush by sucking in a burst of Stormlight. She folded her arms and regarded the others as they—lazily—climbed to their feet and saluted. They were only twelve men now. Some had made their way to other jobs. A few others had died in the Battle of Narak.

She’d kind of been hoping that they would all drift away—if only so she wouldn’t have to figure out what to do with them. She now realized that Adolin was right. That was a terrible attitude. These men were a resource and, all things considered, had been remarkably loyal.

“I,” Shallan told them, “have been an awful employer.”

“Don’t know about that, Brightness,” Red said—she still didn’t know how the tall, bearded man had gotten his nickname. “The pay has come on time and you haven’t gotten too many of us killed.”

“Oi got killed,” Shob said from his bunk, where he saluted—still lying down.

“Shut up, Shob,” Vathah said. “You’re not dead.”

“Oi’m dyin’ this time, Sarge. Oi’m sure of it.”

“Then at least you’ll be quiet,” Vathah said. “Brightness, I agree with Red. You’ve done right by us.”

“Yes, well, the free ride is over,” Shallan said. “I have work for you.”

Vathah shrugged, but some of the others looked disappointed. Maybe Adolin was right; maybe deep down, men like this did need something to do. They wouldn’t have admitted that fact, though.

“I’m afraid it might be dangerous,” Shallan said, then smiled. “And it will probably involve you getting a little drunk.”

Oathbringer: The Stormlight Archive Book 3 copyright © 2017 Dragonsteel Entertainment, LLC