Welcome back to the Gene Wolfe Reread. It’s been a while since we last followed in the footsteps of Severian, who began his life as an apprentice in Matachin Tower and in a short span of time became a torturer, an outcast, a journeyman, a healer, an actor, a lictor, a lover, a father, and, the last time we saw him, someone ready to become a volunteer in the war against the Ascians.

As you may recall, my role in this reread is not exactly the one of a scholar, even though I am also one (as well as a fiction writer and a Gene Wolfe fan, naturally), but of a perplexed reader. When I called my first article of this series “The Reader in the Mist,” I did so to describe what I was feeling then—as a kind of a novice, being just initiated into the mysteries of Wolfe’s fiction.

Rather than toot my own horn as an expert, I wanted to do quite the contrary: to make myself humble. In the course of this reread, I’ve been corrected a few times precisely because in some articles I failed to mention this and that aspect of these intricate tales, and on a couple of occasions I may have misremembered a connection or simply gotten it all wrong—alas, this can’t be helped. I embarked on this path with a purpose, intent on visiting Wolfe’s worlds as if for the very first time, for they are so rich with information that one finds necessary to read them again and again. In the particular case of The Book of the New Sun, as I already wrote about here, I’m revisiting these novels after more than thirty years, so it’s indeed for me very much like the first time.

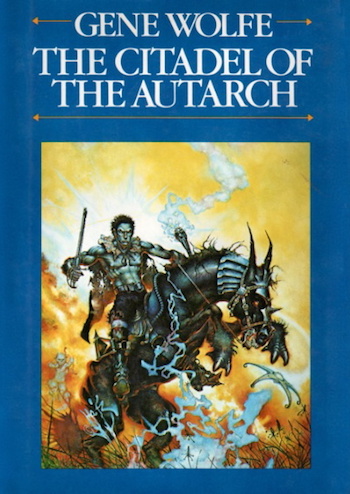

So, we meet Severian again in this, the last book of the Tetralogy (but not the last book in which we’ll see Severian, for our next book is the coda, The Urth of the New Sun). The Citadel of the Autarch is a very intriguing novel. Despite the break over the holidays, I didn’t pause in my reading, and yet I still found this last novel a bit different in tone than the previous three. As far as I know, Wolfe wrote them all linearly in the space of four to five years, so he also didn’t take any significant breaks. But he seemed to have matured along the way, and this shows in the text.

Buy the Book

The Complete Book of the New Sun

The story begins with Severian on his way to the war, only to find a dead soldier on the road. Naturally, he attempts to use the Claw—or what remains of it (recall how the gem encircling the Claw was shattered when Baldanders threw it from the battlements of his castle)—not before, though, taking from the dead man what he had (particularly food, since Severian was starving). He finds among the soldier’s possessions “an onion and a half loaf of dark bread wrapped in a clean rag, and five strips of dried meat and a lump of cheese wrapped in another.” He also takes a falchion, which is a sword with a broad, curved, single-edged blade.

He consumes the food first, but the food is dry and hard and he has some difficulty eating. He eats what he can and reserves part of it for later. He then reads a letter that the soldier carried but never posted, to his lover, telling her about seditionists who killed the sentries of his camp, and how the seditionists call themselves “the Vodalarii after their leader.” Only then does he reach for the Claw and tries to revive the soldier—which, naturally, he does.

The soldier seems disoriented, and says nothing. Severian manages to make him stand up so they can find something to drink, and they take the road. Eventually, they are informed of a lazaret three leagues away where they can find food and rest. He then mentions something interesting:

His face was not really like Jonas’s, which had been long and narrow, but once when I saw it sidelong I caught something there so reminiscent of Jonas that I felt almost that I had seen a ghost.

Later, he tries to make conversation with the soldier, who remains mute, telling him about some of his adventures and his perfect memory. (This part brought to mind Latro, protagonist of Soldier in the Mist. Did Gene Wolfe start to shape that character from the clay of this one, a soldier with no memory of his past? I don’t know for sure, but it seems plausible to me.) But the aspect of this section of the novel that strikes me as most significant is the following monologue regarding the Claw’s actual capabilities—what it really does, instead of magically resurrecting the dead or curing the wounded:

When you brought the uhlan back [Dorcas had told him] it was because the Claw twisted time for him to the point at which he still lived. When you half-healed your friend’s wounds, it was because it bent the moment to one when they would be nearly healed.

Time and memory are the mainstays of Gene Wolfe’s prose—and The Book of The New Sun is (so far in our rereading) the place where all the roads meet and everything seems to make sense, albeit in an odd, non-linear, twisted sense.

Severian continues on with his musings a bit longer, concluding with the following observation:

I don’t know if you believe in the New Sun—I’m not sure I ever have. But if he will exist, he will be the Conciliator come again, and this Conciliator and New Sun are only two names for the same individual, and we may ask why that individual should be called the New Sun. What do you think? Might it not be for this power to move time?

In the Catholic liturgy, Jesus is said to have resurrected at least one person, Lazarus, and cured countless people. Might he not theoretically have had the same power? Even the reported miracles of the multiplication of bread and fish, not to mention the transmutation of water into wine, could be a deft manipulation of the space-time continuum somehow… For the New Sun is an analogue of Christ, and he and the Conciliator are the same person, and it has already been established that Severian, if not literally these men of olden times, is also their analogue—their current incarnation so to speak, and therefore he acts as a Christ figure. This, as the priest says in the moment of the Holy Communion, is the mystery of faith. But here we are witnessing some of those miracles, even if they can be potentially explained through future technology.

Eventually, both men find the camp where the lazaret is located and are welcomed by the Pelerines. The nun that receives them takes their temperature and finds they both have a fever, so she instructs a slave to bathe and feed them. After the bath, Severian finds out that the soldier can speak, and they talk a little. When Severian asks him if he remembers his name, the answer is intriguing, even funny:

I lost it somewhere along the way. That’s what the jaguar said, who had promised to guide the goat.

This appears to be something Jonas would have said, and Severian notices it, though he will only touch on the subject later. For now, though, he goes to sleep—and has a dream that encompasses flashes of the previous volume, from his mate Roche and Master Malrubius to Thecla and to Valeria and the Atrium of Time, and also with Typhon. It offers a very elegant reminder of past events without resorting to clichés like “the story thus far…”

Upon awakening, he starts to appraise the other people lying in cots near him. The first is a man with close-cropped scalp with empty eyes, “emptier than any human eyes I had ever seen.” The man salutes him with “Glory to the Group of Seventeen.” When Severian salutes him and asks him a question, he receives another enigmatic statement: “All endeavors are conducted well or ill precisely in so far as they conform to Correct Thought.”

When I was in my twenties and reading these books for the first time, I recall now that this part unsettled me a great deal. I thought the Ascians must have been an awful people, to have become this sort of forced hivemind, a people that can’t think—pretty much a metaphor for communism or Maoism under Western eyes. Now, in my fifties, I am no longer afraid, but merely saddened by this characterization that, to me, seems much more problematic than Wolfe’s medievally romantic sexism: a depiction that seems to reflect the racism of the colonial mindset. I should note again that these are my impressions upon reading the text, without recourse to the bibliography and interviews of Gene Wolfe. So, my thoughts here on that subject are a matter of subjective interpretation alone, and this should be read—as should this whole series—with a grain of salt.

Terms like “correct thought” remind me of the Noble Eightfold Path of the Buddhism, which is a religion followed in most of Eastern countries, China included—because, being a “religion without god,” as some call them, it should be more pliable to a socialist state. (Not quite, but I won’t delve deeply into this tangent, here.)

Bear in mind, though, that this reading is by no means a condemnation of Wolfe’s work. I still love his writing, I’m still in awe of The Book of the New Sun, and I still have the deepest respect for him. I never met the man in person, but as far as I can tell through friends and colleagues of mine who did, he wasn’t racist or colonialist. Rather, his stories are in no small measure merely a retelling, in some places, of the pulp stories he used to read as a child, which may be the root of this depiction of the Ascians, to some degree. (It’s for no other reason that references to Dr. Moreau’s Island keep creeping up in his work, for instance.)

Also, I now have a newfound appreciation for Wolfe’s use of language in this particular case as well. The use of the phrases from the book used by all Ascians (a reference to Mao’s Red Book) is very deftly done, as we will see shortly, when the character of Foila offers to serve as an interpreter, in a very One Thousand and One Nights fashion (another nod to colonialism, this time Orientalism by way of “exotic” tales, but I can understand this one better because, as many in my generation, I also read a lot of adaptations of this book). Suffice it to say, to finish this (minor) quibble with the way the Ascians are presented, this part still bothers me, but serves as a reminder that no work or person is perfect, although we can still respect them. Onwards.

Severian will meet in this same scene other soldiers: Foila, of the Blue Huzzards, Melito, a hoplite, and Hallvard, “a big, fair skinned, and pale haired” man, who “spoke with the deliberation characteristic of the icy isles of the south. (I perceive the same pulp-y stereotyping at work here with Hallvard, a valiant Nordic warrior, who behaves like someone out of a Prince Valiant comic, and I make a mental note about archetypes).

It happens that Melito wants to marry Foila, and, while she doesn’t seem inclined to entertain this notion, she challenges him and Hallvard to a contest of stories, where the winner might have her hand. She calls for Severian to be the arbiter, and he accepts.

The following stories are for me the best in the entire saga—though I concede I am probably missing some context here, and may need to eventually write a follow-up article on the Tetralogy focusing only the various tales and stories that are embedded throughout this series.

The stories are told to everyone there to listen, including the formerly dead soldier, who still is clueless about his own name, so when Severian introduces him to the group, he calls him Miles, “since I could think of nothing better.” Why this name is chosen, I have no idea. My editor, though

(thanks, Bridget!), suggests me that the name “Miles” means “soldier,” for it’s from the same Latin root as “military,” or “militant,” and I couldn’t agree more.

However, before this contest begins, the two have a talk, and when Severian tells Miles how he resurrected him, the soldier doesn’t believe, attempting to explain it away:

Maybe I was delirious. I think it’s more likely I was unconscious, and that let you think I was dead. If you hadn’t brought me up here, I probably would have died.

Then Severian tells Miles he somehow believe the soldier might be his friend Jonas, changed in some way by Father Inire’s mirrors. He then explains that Jonas told him that he would come back for Jolenta when he was sane and whole:

I didn’t quite know what to think when he said that, but now I believe he has come. It was I who revived you, and I had been wishing for his return—perhaps that had something to do with it.

He tells Miles (who now he calls Jonas) that Jolenta is dead, and even though he tried to bring her back with the Claw, he couldn’t do it. Then the soldier rises, his face “no longer angry, but empty as a somnambulist’s” and he leaves in silence.

On to the stories, then: Hallvard is first, and he tells the story of the two sealer hunters, his two uncles, Anskar and Gundulf. Since Hallvard’s father had gotten the dowry that came to him via his wife, the grandfather decided that all that he had would go to the uncles when it came time to dispose of his property. One year later, the two went to the ocean to fish, but only Gundulf returned. He tells the others that his brother cast his harpoon to kill a bull seal, but a loop of the harpoon line had caught his ankle and he was dragged into the sea. Gundulf tried to pull him back, but he couldn’t, and he could only save himself by cutting the line with his knife.

Then, one morning, some children saw a seal laying on the shore of a bay nearby. Seals only come to land when injured, so the man of the village ran there. But what they found instead was a dead man, preserved by the cold sea brine. It was Anskar, still tied to the rope that had been cut. When Gundulf saw the body of his brother, he cried and ran away into the dark. The men ran after him and captured him. It turned out that Gundulf had fallen in love with a woman on the big isle named Nennoc, and she had borne a child by a man who had died the winter before, so no man would have her. But Gundulf would have her, and so Anskar called him oath-breaker. So Gundulf threw him overboard and snapped the rope free. But Anskar took his knife and, even in the cold water, used it to cut the rope so the men would know that he had been murdered.

After Hallvard’s story, it was getting dark, so they all went to sleep for the night. But one of the priestesses came and sat by Severian’s cot. She tells him that the resurrected soldier had remembered his name, but when Severian asks her what name is this, she says “Miles,” the name Severian has given him. Then they begin discussing Hallvard’s story, which she had overheard, and talking over the nature of good and evil, and of authority. Then Severian tells her he is from the guild of Seekers for Truth and Penitence, and she says that he believes he possess the Claw of the Conciliator; Severian takes out the Claw and give it to her, saying: “With this you can save many. I did not steal it, and I have sought always to return it to your order.”

She hears his story with compassion, but she does not believe him. She tells him that the Claw was a large gem, a sapphire, not this little black claw he’s given her, and more:

As for its working miraculous cures and even restoring life to the dead, do you think our order would have any sick among us if it were so?

She’s got a point there. I have been thinking for quite some time now that in fact this power belongs somehow to Severian and Severian alone, for he is the New Sun. Here the narrative may stray from science fiction and veer off into fantasy, I’m not sure—I reserve the right to be kept in the sense of wonder that characterizes the narrative, for the time being.

Immediately after the Pelerine leaves, a sick man calls for Thecla, for he heard Severian’s voice, but somehow he has also heard the voice of the woman whose flesh Severian had consumed at Vodalus’s feast. Severian also manages to make this man gets better, and right after that we hear with him Melito’s story.

Melito tells the story of a fine farm especially noted for its poultry, and of the farmer, who had the strangest notions. Among other things, he didn’t caponize the young cocks, but let them run free and grow up, until they eventually fought each other for dominance. The best, as he saw it, would will, and go on to sire many more chicks to swell his flock.

So, the cock of his flock was indeed a very fine one. Young, strong, brave, with breast of glowing scarlet and strong wings. He had a thousand wives, with one hen as his favorite, and he used to walk proudly with her between the corner of the barn and the water of the duck pond. (At one point Melito compares the cock to the Autarch himself, among other things because “the Autarch is a capon, as I hear it.”)

One night, a great owl breaks into the barn where the chickens roosted and seizes only the favorite hen of the cock. As the owl is getting ready to fly away, the cock appears in a furious frenzy and attacks the owl with spurs and bill, forcing it into retreat.

The cock had a right to be proud, but he now became too proud for his own good. He began bragging, talking of rescuing the prey of hawks and other things, and refused to listen to anyone who didn’t agree with him. When at last the dawn began to break, he rose and perched himself atop the weathervane on the loftiest gable of the barn, and he screamed again and again that he was lord of all feathered things. He crowed so seven times, and, not content, made the same noisy boast an eighth time, finally flying down from his perch.

Then an angel came down from the heavens, a marvelous collection of glorious light and wings of red, blue, green and gold, and the angel tells the cock:

Now, hear justice. You claim that no feathered thing can stand against you. Here am I, plainly a feathered thing. All the mighty weapons of the armies of light I have left behind, and we will wrestle, we two.

At that the cock spread his wings and bowed low, telling the visitor that he could not accept the challenge, because the angel only had feathers in his wings. But the angel touches his own body, which is immediately covered entirely in feathers. The cock’s second excuse is that, since the angel can clearly transform himself in any creature he wishes, the cock would have no guarantee of fair play. And again the angel complies, tearing his breast open and removing his shapeshifting ability, handing it to the fattest goose of the barn. The third problem raised by the cock is that since the angel was clearly an officer in the service of the Pancreator, the cock would be committing a grave crime against the only ruler brave chickens acknowledge.

Then the angel tells the cock he has just argued his way to death. The angel would have done nothing more than twist his wings back a bit and pull out his tail feathers. Now, however, his fate will be different: he lifts his head and gives a strange, wild cry. Immediately an eagle comes down from the sky and attacks the cock. After a while, the cock, very wounded, seeks refuge under an old cart with a broken wheel, and the angel says:

“Now (…) you have seen justice done. Be not proud! Be not boastful, for surely retribution will be visited upon you. You thought your champion invincible. There he lies, the victim not of this eagle but of pride, beaten and destroyed.”

The cock, though, is not defeated yet. He tells the angel that, though he is broken in body, he is not defeated in spirit; he is willing to accept his death at the angel’s hands, “But, as you value your honor, never say that you have beaten me.”

The angel replies:

The Pancreator is infinitely far from us (…) And thus infinitely far from me, though Ifly so much higher than you. I guess at his desires—no one can do otherwise.

Then he opens his chest again and replaces the shapeshifting ability. Then he and the eagle fly away, and for a time the goose followed them.

Thus Melito finishes his story and Severian says he is going to need time to think about both narratives, to which Foila tells him: “Don’t judge at all. The contest isn’t over yet.” Everybody seems surprised, but she tells them that she’ll explain tomorrow.

That same evening, Severian’s supper is brought by a postulant, Ava, with whom he talks a bit, and finds out she lived near the Sanguinary Field and witnessed his duel with Agilus. This time, the subject of his conversation with a Pelerine is ethics: he asks her if she isn’t bothered by the fact that the soldiers they care for have been doing their best to kill Ascians. Her answer: “Ascians are not human”.

The entire dialogue is complicated, because Severian doesn’t quite disagree, merely points out to her that they are not to blame, for they had their humanity stripped from them. Then he grips her arm, feeling a barely containable excitement, and asks her:

Do you think that if something—some arm of the Conciliator, let us say—could cure human beings, it might nevertheless fail with those who are not human?

He also tells her about the alzabo potion and Thecla, and about the Claw. Ava tells him that she is familiar with the corpse-eaters (as she names the people who partook in the same kind of banquet Severian did with Vodalus), but they don’t behave at all like him. She asks him if he really had the Claw with him, and when he says he had, she says:

“Then don’t you see? It did bring her back. You just said it could act without your even knowing it. You had it, and you had her, rotting, as you say, inside you.”

“Without the body…”

“You’re a materialist, like all ignorant people. But your materialism doesn’t make materialism true. Don’t you know that? In the final summing up, it is spirit and dream, thought and love and act that matter.”

This last sentence might well be the most significant of the entire series, and I intend to return to it later. For now, suffice it to say that Severian once again is led to consider that, with or without the Claw, only he has the power to heal and to bring back the dead, be they in their own bodies or not.

I will leave you now, before we learn about Severian’s judgment of the narratives. If you’ve read these books, you know that there’s more to it—but I won’t say anything else for the moment. If you haven’t, you’re in for a few surprises yet.

I will be waiting for you all, then, on Thursday, February 6th, and the second installment of The Citadel of the Autarch…

Fabio Fernandes started writing in English experimentally in the ‘90s, but only began to publish in this language in 2008, reviewing magazines and books for The Fix, edited by the late lamented Eugie Foster. He’s also written articles and reviews for a number of sites and magazines, including Fantasy Book Critic, Tor.com, The World SF Blog, Strange Horizons, and SF Signal. He’s published short stories in Everyday Weirdness, Kaleidotrope, Perihelion, and the anthologies Steampunk II, The Apex Book of World SF: Vol. 2, Stories for Chip, and POC Destroy Science Fiction. In 2013, Fernandes co-edited with Djibrilal-Ayad the postcolonial original anthology We See a Different Frontier. He’s translated several science fiction and fantasy books from English to Brazilian Portuguese, such as Foundation, 2001, Neuromancer, and Ancillary Justice. In 2018, he translated to English the Brazilian anthology Solarpunk (ed. by Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro) for World Weaver Press. Fabio Fernandes is a graduate of Clarion West, class of 2013.