A woman visiting Las Vegas for a fun weekend encounters her ne’er-do-well ex-husband, who begs her for a favor that gambles with life and death…

I put off the unveiling of my daughter’s headstone as long as I could. We didn’t do it until the eleventh month after she died, when the yahrzeit was in sight and I couldn’t stall any longer. I made all kinds of excuses—my grandchildren weren’t ready; I was too busy getting them settled in with me and Phil to organize it; it was too cold for us all to stand outdoors. Finally my sister Sadie called me up and told me it had to be done, it had to be done soon, and she would organize everything. Sadie is my older sister. My other two sisters are younger than me, not that any of us are young anymore. Betty was the youngest of us, the baby of the family, but she died of cancer twenty years ago during the war, so it’s just the four of us left.

Sadie took care of everything—she got in touch with the rabbi at my shul, she sent out the invitations, she had our other two sisters, Millie and Rose, put together some food and desserts and bring them to my and Phil’s apartment for afterward. I didn’t have to do a thing. I just told her to send any bills to Phil, and he would take care of them. And he did, without a word. He’s good like that. Reliable.

So all I had to do was show up on Phil’s arm, with my daughter’s children, Elsie and Danny, in tow, all of us dressed soberly and formally. That I could do, down to Elsie’s white gloves. Only twelve years old, and already her hands were too big to borrow a pair of mine. But I made sure she had her own.

I don’t remember what the rabbi said about Myra after reading from Psalms. He didn’t know her too well, anyway. He was the rabbi from my synagogue near Sutton Place. Myra and the kids had lived out in Midwood. Instead of listening, I thought about the last message she ever sent me, and wondered if it was my fault she was dead.

I didn’t listen to the Kaddish, either. Instead I looked at the chanting men through Myra’s eyes and saw what she would have seen, what would’ve mattered to her. Her father was missing.

Of course, he’d been missing for a long time by then.

I’d married Harry in 1927, and I’d married him for love, and my, weren’t we in love? We used to go out drinking and dancing together in smoky speakeasies. I’d line my eyes all dark with kohl—they used to call me Cleopatra—and he’d play the ukulele. In the summer, we’d take the trolley out to Coney Island and lie on the beach together and stroll on the boardwalk and stop to smooch each other every few minutes.

Love.

Harry, he was so handsome. Even after I knew he was no good, I couldn’t keep my hands off him. He had thick, dark, curly hair and sparkling dark eyes, and a knowing, cynical smile that just made me weak. A nice sharp jawline. Phil, now, he never really set my blood pounding like that, but on the other hand, he’s never raised his voice, either, to me or to Myra, not even to his own boys. Harry had a mean streak. Myra got that from him.

We loved each other so much, we got married and kept up the smooching, and in 1929 I had a little girl. I had Myra. He named her that.

Then a few years later, I got sick, real sick. Women’s problems, they called it, though I blame it on Harry’s whoring around. That’s love for you. First I had to stay in bed and I only got up when Myra needed me. Then I had to take Myra and go to my mother’s so she could take care of us both. Harry was working too hard to do it, I told her. Pfft. As if Harry was ever a working man. He was a gangster, that’s what he did, and he wasn’t very good at it. Sure, we got a warm reception at all the joints he supplied liquor to during Prohibition, but it turns out that doesn’t matter so much when you’ve got a kid you’re trying to feed.

Anyway, where was I? Right, I took Myra and went to Mama’s so she could take care of us, and then things got even worse, and Myra had to stay with Mama and Papa and Betty, who was still living at home, while I went to the hospital.

Poor Myra didn’t like that. Mama said she cried and cried after the ambulance had taken me away. Poor kindele. Mama always thought maybe that was why Myra was the way she was, the ambulance taking me away, and her not being allowed to visit on account of her being a child. But I don’t think it was that. After all, I came back, didn’t I?

But we didn’t know you would at the time, Mama would always say when I said that. And she was right. Things looked real bad for me for a while. We didn’t know if I was going to make it. And Harry, well, I guess he didn’t relish the thought of being a widower with a small child the way things were—this was just thirty years ago, 1932, the Depression—and sometime in there he just . . . left. Didn’t turn up one Friday night to have Shabbos with Myra—Mama always kept the sabbath at her home—and we didn’t hear from him after that.

So there was Mama with Betty and Myra at home and Harry had vanished, and things didn’t look so good for me. Mama didn’t know what to do, maybe change my name again, like when I was little and had scarlet fever and I went from Henrietta to Josephine. But then Mama remembered that wasn’t what had helped. What had helped was when she talked to a woman who had just come over from the old country, a witch, I guess you’d call her, and the witch had made me a broth and an amulet both. So Mama went to the witch again. Tante Deborah, I call her.

Mama left Myra with Betty and brought Tante Deborah to visit me in the hospital, and I remember sipping something that tasted terrible, and Tante Deborah slipping a pouch under my pillow and chanting some words I was too sick to hear well or follow—Hebrew, I think. And after that I started to get better. The doctors at the hospital, they couldn’t believe it, and the nurses told me later that they’d never seen someone so sick get well again. And finally I could go home.

Harry had been gone for weeks by then.

Myra was never the same after her beloved Papa left . . . I think she never got over it. She cried more easily than ever, and even when she wasn’t crying, she was mostly unhappy. I don’t know, those were bad years. Hard years. I worked at Gimbels, a window dresser, and Myra and I lived with Mama and Papa and Betty. I’d go without dinner sometimes so there would be enough for Mama and Papa and Myra. Our other sisters couldn’t help, nobody was any better off. For years, this went on. It was no way to live.

I couldn’t stand it, I told Mama. “We can’t go on like this,” I told her. “Papa out of work, Betty and I don’t bring enough home.”

“Well, what else is there to do?” asked Mama.

I thought about Gimbels. “I’m gonna catch myself a rich man,” I told her. “The very next one who comes into the shop. I am.”

And I did. Spotted Phil when he came in looking for clothing for his sons. A respectable widower, his wife had been gone for a couple years, and I could tell that he was looking around again. He seemed gentle, and he seemed kind enough, and he had money. You can’t ask better than that. He came back to shop now and then—for shirts, ties, gloves, this and that, and finally he asked for a date. It took maybe . . . a year after that until he proposed. I said yes, but only if we moved into Manhattan, because I didn’t want to live in Brooklyn no more, even at his very fancy house in Crown Heights. They wouldn’t sell to Jews on Fifth Avenue in those days, or even near it, so that’s how we ended up on Sutton Place, a co-op in a real fancy building, with a white-gloved doorman downstairs. And we’ve been all over together, on cruises, to resorts—all very nice. And I never went without dinner again, even on Yom Kippur, because I’d had enough of fasting. And Myra slept in a real bed, not a hammock.

Love. Well, I learned to love him.

His boys never did like me much, though. I think they thought I was a gold-digger. Maybe I was, but what else was I supposed to do to take care of myself and Myra? And Phil’s been happy. I can count the number of fights we’ve had on one hand. I pay attention to his favorite colors, and get my dresses made up in them. I pay attention to what he likes to eat and make sure it’s always on the table. He tells me where he wants to go for vacation, and I set everything up. I didn’t do all that with Harry. But I’ve kept Phil happy for almost twenty-five years and counting, and that’s not nothing, either.

Myra never took to him. He wasn’t unkind to her, but he never made much of an effort, either. What man does, when it comes to children? Especially children that aren’t his. For Myra, nobody could replace her adored father. She remembered dancing with him while she was little, she remembered that he was handsome. I’d be surprised if she remembered anything else. She thought she remembered why Harry left, though. She blamed me for it, for driving Harry away. I was sick at the time, so sick. It didn’t make any sense, but she blamed me anyway.

Never mind Harry. It was Phil who paid for her medicines, and Phil who gave me the money to support her and the kids after her husband, Siggy, left, and Phil who paid for her funeral and put his arm around me by the graveside, and Phil who held my elbow at the unveiling. Harry was nowhere to be seen, just the same as the last thirty years.

Phil wasn’t there on Myra’s yahrzeit, a month later, though. He had a business dinner that evening, but I didn’t mind. There was something I had to do that night, besides lighting the candle, and I didn’t want to explain it.

After the kids were in bed, I opened my jewelry box in the bedroom I shared with Phil and took out the envelope with the last note from Myra. I hadn’t told anybody about it, not my sisters, not Phil. He knew it existed, of course, but what it said? No. I couldn’t. I didn’t tell anybody.

I read it one more time, read the accusations about me, the way she blamed her daughter for ruining her life. Then I took it to the living room and held the corner of it in the flame of the candle until it caught. I held it for a few moments more, until it was well and truly aflame, and then I dropped it into an ashtray and watched it burn.

It was a couple months later that I was playing canasta with my sisters, and Sadie had the idea for us to go to Vegas. The grandkids hadn’t come home from school yet, but the seven-layer cookies were out on the table already, and we were munching on them.

“Phil’s gonna be out of town on business for two weeks next month,” I said, as I rearranged my cards and laid down a set of nines. “And the kids are going to visit their father in Philadelphia for one of those weeks, you know. It’ll just be me here.”

All three of my sisters exchanged looks. They thought I didn’t see, but I did.

“That’s lonely,” sympathized Rose. “Maybe one of us should come stay with you.”

“That’s a break,” corrected Sadie. She was my partner in the game. She put down a canasta of aces and smirked.

“Nice,” I said. Sadie is better at canasta than me, but I’m better than Millie or Rose.

“You should go somewhere,” Sadie continued. “Why let them have all the fun? Lock up the apartment and you take a trip also.”

I wasn’t sure my grandkids, Elsie and Danny, would describe visits to their father’s house with his new family as fun, but I didn’t say that. Well, I say “new,” but he and his wife have a three-year-old, and I hear she’s expecting again.

“Ach, where would I go?” I said absently. I was watching Millie rearrange her cards, trying to figure out what she had in her hand.

Sadie rolled her eyes. “Vegas, of course! You love Vegas.”

I do like Vegas. We’d been there a few times and while I enjoy canasta with the girls, blackjack is really my game. When I say “we,” I mean me and Phil, of course. Harry and me, we never had money to go anywhere farther than the speakeasy on Ludlow Street.

Millie drew a card and discarded another. I eyed the discard pile, but decided against picking the pack. I didn’t want to get saddled with that many cards this late in the game.

“Vegas alone,” I said, “is not necessarily a fun time.” I drew a card. It was the three of hearts, so I smiled and put it down with the two other red threes I had.

“So, who says you’ll be alone?” countered Sadie. “Take me with you. Your Phil can afford it.”

I had done the best of all of us. My Phil certainly could afford for Sadie and me to go to Las Vegas on his dime. Our dime, I should say. Haven’t we been married long enough for me to say that?

“We-e-e-e-ell,” I said. “Why not? Only what if Elsie and Danny need to come home early? I’m not going to go for the whole break.”

Elsie and Danny don’t like their stepmother, and I don’t think she much likes them. She wants to pretend that Siggy came to her fresh and new, no previous family at all, certainly no kids hanging around after they’re no longer wanted, kids from a marriage she helped break up. I don’t know how many more visits to Philadelphia are in the cards for Elsie and Danny.

Speaking of cards, Millie laid out what remained of her hand. “I’m out, girls,” she said. “Time to count up your points.”

So the next month, Phil packed for Montreal, Elsie and Danny packed for Philadelphia, and I packed for Las Vegas. After I’d said good-bye to Phil and he’d headed off to Canada and after I’d kissed Elsie and Danny good-bye and they’d driven off in the backseat of their father’s car, I picked Sadie up in a taxi and we got on a plane to Nevada. We took a taxi from the airport to the Stardust Resort and Casino. It was very nice in there, all red and brown velvet, very plush. Anyway, when we got there we each went to our own room and unpacked. Our rooms were in the Venus building. Love again.

You gotta understand how fancy Vegas was back then. It was adults only, not like porn, but like a fancy restaurant. I’d packed my fanciest gowns, and even bought a couple new ones for Sadie so she wouldn’t feel outclassed. Sure, we knew the place was mobbed up and had been since the ’40s, but so what? To tell the truth, it made me feel a little more at home, because the mob there was mostly our guys—Yidn, you know? And it made the place very safe—you never had to worry about anything violent happening, because the boys didn’t want to give authorities any excuse to take a closer look at what they were doing. All you really had to worry about was one of the boys getting too handsy, but where don’t you have to worry about that?

Sadie and me, after a late lunch at the Polynesian restaurant they had there—I don’t know what that had to do with the outer space theme, but that was the restaurant they had—we went straight to the casino in our very nice dresses, faces all made up. Sadie, she played around at the slot machines, the roulette wheel. I went straight to the blackjack tables. I picked one at random and just stood and watched for a few hands.

Then I placed a few small bets, nothing crazy, just feeling out the game and the players, and I did all right. Before long, I took a chair myself. I won a few hands, lost a few, but I was doing better than breaking even. Just a little better, but that’s what you go for in blackjack. Watching the cards, I forgot to think about Myra for a little while. At some point I looked up and saw that Sadie had floated over and was watching me.

I caught Sadie’s eye and jerked my head slightly. She floated a little nearer.

I threw the next hand and busted. Then I looked at the little gold wristwatch on my left arm. With my eyes, I can’t actually read it, but I didn’t have to.

“Sadie, hon,” I said. “I’m getting hungry. It must be dinnertime, don’t you think?”

A few older gentlemen offered to take us to dinner and the evening show—Sadie and me, we weren’t young anymore, not by a long shot, but we were still pretty good-looking for our age. We waved them off, politely of course, no hard feelings, but we were planning a quiet night. Well, I was.

Sadie had different ideas. “Whaddaya mean, a quiet night? It’s not every week we get to Vegas!”

“I get tired early these days,” I told her. “With Elsie and Danny, I’m raising kids all over again, but I’m not so young this time.” Honestly, I’d been tired ever since losing Myra.

So we split the difference. We had dinner in my room—room service—and after some coffee so I wouldn’t doze off, we went back down to the evening floor show.

First, though, I placed a long-distance call to Siggy’s in Philadelphia. He picked up.

“Siggy, it’s Josie. How are the kids doing?”

“They’re doing fine,” he said, but he didn’t sound so sure. “Having the time of their lives.”

“Yeah?” I said. “That’s good. Get Elsie. I wanna say hi.”

After half a minute, Elsie got on the phone. “Hi, Nana.”

“Hi, darling,” I said. “Are you having fun?”

Elsie paused just a little too long before answering. “Yeah.”

“What’ve you and your brother been doing?” I asked.

“Nothin’.”

“Nothing?”

“We all went for ice cream.”

Ice cream. I could get her ice cream in New York.

“Is Faye being nice to you?” I asked.

“Uh-uh.”

I sighed. No point in asking what that bitch was doing this time. Elsie wouldn’t be able to say on the phone in front of everybody.

“Well, darling, listen. Your Aunt Sadie and me will be home in a few days, and then if you want to come home early, you just say, all right? I’ll take the train down and come get you.”

“Okay, Nana,” said Elsie.

“Now put me back on with your father.”

I warned Siggy to take good care of the kids and then hung up.

The Stardust floor show was known for its topless showgirls, which I guess was something for the guys to get excited about, but didn’t mean anything to me. I enjoyed the fruity sweet cocktails, though—they reminded me of the drinks I’d get when Phil and I went on cruises. I might’ve had one too many, though, because on my way to powder my nose, my head started spinning and I had to sit down in a small private booth.

A man slid in across from me, so quickly and smoothly that he must’ve been following me, so my stomach tightened and I got ready to kick up a fuss if he gave me any trouble. I hoped Sadie was okay at the front-seat table where I’d left her.

The man tilted his face to the side quizzically. “You don’t recognize me, Josie-Jo? I haven’t changed that much, have I?” He smiled at some joke I wasn’t in on, I guess, and then I knew him.

“We got nothing to say to each other, Harry,” I said icily. “You made sure of that thirty years ago.”

“Oh, don’t be like that, Josie-Jo,” he said. “I can see you’ve done all right for yourself, in the end—jewels like those on your neck and fingers, and I saw you cleaning up at the blackjack table earlier. You’re not still sore, are you?”

I ignored his question. “You’ll excuse me, Harry. I’m just on my way to the ladies’.”

“Just sit with me for a minute,” he said. “It’s not often I get to sit with a fine-looking lady like yourself. You do look good, Josie. If I didn’t know better, I’d swear you weren’t yet fifty.”

“Shut up, Harry,” I said. “I’ve already talked to my former son-in-law today, and I don’t need another useless deadbeat.”

“Josie-Jo, c’mon. Have one drink with me. Just for old times’ sake. You go powder your nose, and I’ll wait right here for you. Just one drink. Please.”

“Don’t bet on it,” I told him. I tried to sweep majestically out of the booth, but I stumbled over my heels and almost fell against the table. I stalked to the ladies’ room, glancing back only once.

After I’d taken care of my business, I looked at myself in the mirror in the ladies’ lounge. Harry wasn’t wrong, I was looking good that evening. And he was easy on the eyes, too. He always had been. Come to think of it, he’d looked a lot younger than I would have expected. I’d just turned sixty, and if Harry had been a stranger on the street, I would have put him at forty-five at the most. I sighed and patted my hair. He was still a handsome man, there was no denying it.

What harm could one drink do? Maybe I’d finally give him a piece of my mind about what his leaving had done to Myra.

I patted my hair back into place one last time and walked out of the ladies’ room and back over to the table.

“Okay,” I said, sitting down. “One drink.” I ordered a mai tai, a drink I’d tried on the last cruise I took with Phil, before Elsie and Danny had come to live with us.

“You don’t drink sidecars anymore, Josie?” Harry asked.

“A lot about me has changed,” I said.

“I guess I don’t know that much about you, now,” he said.

“That’s a fact,” I said, and he winced.

“But maybe you still have some fond feelings for me,” he said. “You know, just for old times’ sake. Maybe you still care a little.”

The girl brought the mai tai, saving me from spitting out the swear words on my lips. I swallowed them politely, instead, along with a sip of the drink, and by the time the girl left, I had myself under control again.

“Fat chance,” I said, and lit a cigarette. “What is all this about, Harry? You need money? I’m not giving you any.”

“I don’t need money, Josie-Jo.” Suddenly Harry looked very tired, though still younger than he had any right to look. “I don’t need money anymore.”

“Don’t be ridiculous, Harry,” I said. “Everybody needs money. What’d you do, marry an heiress?”

“No,” he said. “I died.”

“You did what?” I asked. I must’ve misheard, I thought.

“I came out here because I needed money. Wasn’t too popular with the boys in New York in the ’40s, on account of some deals that went south, which were not my fault, but I was the one that got hung out to dry.”

“Of course, Harry,” I said, and this time I was the one who felt tired. “Nothing’s ever your fault.”

He cracked a smile. ‘Nah, there’s plenty that’s my fault, Josie. But not those deals. I was set up, is all. I’ve got my suspicions as to who by, but that doesn’t really matter any more. What matters is that I came out here maybe ten, twelve years ago, just after they built this place. I dunno, I lose track of time where I am.”

I rolled my eyes a little. I wasn’t buying it.

He ignored it and kept on with his story. “I was working here, set up in the back room. I did a little of everything that needed doing, and I saw how easy the money was coming in, how much of it there was. My fingers got itchy.”

“Harry.” I sighed. “You know better than that. Everybody knows better than that.”

“Well, hell, Josie-Jo, there was so much of it, and my cut started to look so small. I figured, I’m the one who says how much is coming in, nobody’ll notice if I skim a little, if I run a few games on the side. Who was it gonna hurt?”

“You tried to cheat Lansky? You’re an idiot, Harry.”

“Ain’t that the truth,” he said. “In the end, a couple of Syndicate boys took me upstairs and I didn’t come back down. They’re not supposed to do that here! No violence, everybody knows.”

“Everybody knows not to cheat Lansky, too.”

“And you see how many mirrors there are here. And I had nobody to cover them, like you’re supposed to when somebody dies. Nobody to say Kaddish for me because nobody who cared about me knew I was gone. I was all alone here.”

Suddenly a picture of Myra’s face appeared in my mind, the one person I knew who had always cared that her beloved father was gone, and I remembered covering the mirrors in her house and my and Phil’s apartment after I saw her body. Never had understood that custom before, but after Myra was gone, I couldn’t bear to look at myself and know I was in the world and she wasn’t, and it finally made sense to me.

“I hung around here just a little too long. Just a little too long, and pfft.” He snapped his fingers. “Lilith sucked me right through the mirror. Mirrors—they all lead straight to Yenne Velt, the other world. That’s why you gotta cover ’em when someone dies, new spirits get confused real easy and go the wrong way. Now I’m stuck in some kind of casino there with the shedim, and Josie, I hate it there. It’s awful.”

I realized that I had been listening, transfixed. I shook my head to clear it. “Bullshit, Harry. You’re a bullshit artist and this is bullshit. I don’t know what you want from me, but this is bullshit. I never should’ve married you.”

“Ah, don’t say that, Josie-Jo.” He looked strained. “We had some really good times together, didn’t we? Back when we were young? And we sure made a beautiful little girl, didn’t we?”

“Myra,” I said through clenched teeth.

“Yeah,” he said. “How is the kid?”

So I smacked him. I didn’t mean to, I didn’t even decide to; my hand just flew out before I knew it. But it went right through his face without stopping. I tried it again, and again my hand went through him like he was nothing, like there was nobody there.

He smiled at me, a tired smile, not his usual smirk, and shook his head. “I’m a ghost, Josie-Jo,” he said. “You can try it as many times as you want. But I’m just smoke and mirrors. I’m dead, Josie. I’m not bullshitting you.”

I leaned back against the wall of the booth and said nothing.

“Why’d you want to hit me, anyway?” he asked.

I blinked at him and wondered if I was crazy. I hoped not. Who would look after Elsie and Danny then?

“Why did I hit you?”

“Why did you hit me?”

“I would think you would know, with being a ghost and all.” I took a deep breath. “Myra is dead.” I still didn’t like to hear my voice saying it out loud.

Harry passed his hand over his eyes, and then he looked even more tired than before. Maybe a little older, too.

“I’m sorry, Josie. I didn’t know. When?”

“A little over a year ago.”

“I’m sorry. What happened?”

Yeah, you’re sorry, I thought. For all you would’ve known or cared, she could’ve died when she was seven and got polio. To hell with you. I wished I could’ve connected when I hit him. I wished I could’ve used my fist.

“Fuck you, Harry.”

“Listen, Josie—”

“I’ve got to go. I’m sorry you’re a ghost, or whatever you are, but that’s not my problem.”

He moved to grab my hand, but his fingers went straight through me. My arm felt cold where it had happened. I guessed he really was a ghost.

“Please, Josie. Please. It’s all gray there. No color at all. Nothing living. And no other people, just shedim. And I can play whatever, roulette, blackjack, slot machines, it doesn’t matter, Josie, because I always win.”

I snorted. “Sounds terrible.”

“No, Josie, you gotta believe me, it is. Nobody talks to me. The dealers just look straight through me. Nothing ever happens that I don’t expect. I pick red seventy-two, the ball lands on red seventy-two. I play poker, and I get a straight flush, first hand. I try to throw games, and I can’t. I win. I just wander around, winning and winning and there’s no excitement to it at all, and nobody to talk to, nobody to celebrate with, just endless gray casino chips.

“And I’m trapped there. I need someone to help me, someone living. I need you, Josie.”

Tough shit, I thought. I have some friends, ladies at my shul with numbers on their arms. They come to lunch sometimes, they tell me things in whispers. We stop talking when Elsie and Danny come in the room. They should never know, please G-d. A spirit casino didn’t sound that bad to me. I lit another cigarette.

“So, you want me to spring you? Not a chance, Harry.” But I didn’t walk away. Maybe I should have. But it was nice to be looking at his face. Myra had always looked so much like her father.

“No, nothing like that. You just have to do what you came here to do. Play cards. Play blackjack.”

“Good-bye, Harry.” I stood up.

“Please Josie. I won’t be able to come to you awake again. I want to go on to whatever should come next for me, whatever would’ve come next if the mirrors had been covered, if I’d’ve had someone to say Kaddish for me. Not for my sake, I know I’ve lived a bad life and I wasn’t good to you. But for Myra’s sake—we loved each other once, Josie, Myra showed it, she’d have wanted you to help me out. Even if I become a gilgul and have to come back as a dog or an ant, I just don’t want to be stuck here anymore.”

I shrugged, but at the same time I thought of Harry, young, laughing with me, him with his curls and me with heavily kohled eyes in a local speakeasy. He’d always hated being bored more than anything. Myra had been that way, too.

“Maybe,” I said.

“It’ll happen in your dreams,” he gabbled hastily, like a man who knows his time is short, though the way I figured it, he had nothing but time now. Maybe I was the one running out of time.

“Dreams,” I echoed, watching Harry fade away, like a trick of the light. Only his cigarette still burning in the ashtray. I stubbed mine out next to it and went back to my sister.

“You were gone an awful long time,” she said. “Do you know how many men I’ve had to fight off? ‘My sister’s sitting here.’”

“Sorry, Sadie,” I said. “I ran into Harry.”

“That no-goodnik! Of all people! I can’t believe you gave him the time of day—I always told you he was useless, a schnorrer.”

“You were right,” I replied absently.

She took another look at me. “You don’t look so good,” she said. “You want to go upstairs, turn in?”

“No,” I said. “Let’s stay up late.”

I don’t take sleeping pills, but liquor has a pretty strong effect on me, and I drank more than a little that night. I went down like a chopped tree at the end of it, and I slept sound.

No dreams. I never dream when I drink.

But I pay for it. I was sick all the next morning and my head hurt worse than anything. I couldn’t do this for three nights.

After throwing up, I looked at my face in the bathroom mirror. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Harry’s reflection behind me. His lips formed the word “please.”

When I looked behind me, though, there was nothing there.

I cleaned up at the blackjack tables again that night, and I thought about celebrating with a mai tai, but my stomach gave a lurch and I decided against it. Instead I took my winnings and made an early night of it.

That night, I dreamt that I woke up to find a young red-haired woman sitting on my bed, and me in my nightgown.

“The Lady,” she said, just like that, capital letters and everything. “Is extending an invitation to you. To play blackjack.” I sat up in bed and looked closely at her. She was dressed like a bellhop. Out of some half-remembered story, I quick looked down at her feet. They were bird’s claws.

I woke myself up on purpose, and when I did, I was covered in sweat. I stumbled into the bathroom to get some water, and there was a word written in condensation on the mirror. It was “please.” But I didn’t see Harry, and the word faded after a minute, the way steam does.

That morning at breakfast I couldn’t stop thinking about Myra. How much she looked like her father. How much she had longed for her father. How mean she had gotten, toward the end. Mean to Elsie. Mean to me. And now gone. Not mean to anyone anymore, not ever again.

She never would’ve been mean to Harry, though. I could almost hear her voice, telling me to go help her father.

So I snuck one of those little jars of jam they have at hotel breakfasts into my pocketbook. Demons love jam, everybody knows that. The day before Phil and I had all our stuff moved into the Sutton Place apartment, I put down a dish of jam to make sure any demons hanging around felt good about us, just like my mama taught me, and it worked, we never had a worry about that apartment. I also made sure I had a couple hundred dollars’ worth of chips in my pocketbook too. That evening, before I went to sleep, I put the pocketbook next to me in bed. There was plenty of room. I like to sleep alone in a big bed, and I don’t get to do that too often. Before Phil, I shared a bed with Betty, and before that Harry. And before that, well, we girls slept in hammocks when I was little.

I was awakened from a deep sleep, not by the bellhop girl, but by Harry. I was in bed with the covers up to my chin, thank goodness.

“Please, Josie,” he said. “Please come with me.”

I thought about Myra, and I sat up, still clutching the covers to my neck. “You turn your back until I get my dress on,” I said.

“Are you serious?” he asked. “I’m your husband.”

“Ex-husband. Turn your back.”

While his back was turned I put on a dress and pinned my hair up, but I decided I didn’t have time to put on makeup. I picked up my pocketbook.

“I’m ready now,” I said.

He turned around and smiled a bit wanly. “Beautiful as ever, Cleopatra.”

I smiled back before I thought about it, but then stopped. “Don’t call me that,” I snapped. “Let’s get this over with.”

He led me over to the full-length mirror on the closet door, took my hand and started to step through it, but I hung back, suddenly afraid.

“How will I get back?” I asked. “What if the shedim keep me there?”

He cocked his head. “But you’re alive, Josie,” he said. “I’m dead, no living body to come back to. But you, you’re sleeping safely tucked in bed. Just look.”

I looked back, and there I was, snoring gently in bed, covers pulled up to my chin. “Then how—”

“You’re sleeping, that’s how come you can come with me through the mirror. And your body will draw you back.”

He placed one foot through the mirror, into a deep silver pool, and drew me after him.

We came out in what looked like the casino downstairs, but drained of all color, just shadows and grays. My body, my dress, my pocketbook . . . I was the only patch of color in that place, and it seemed deserted, not a gambler in sight.

“Where is everybody?” I asked, and it came out as more of a whimper than I would’ve liked.

“Don’t worry, kid,” Harry said warmly, and drew my arm through his. “You’re safe.”

There were dealers at all the card tables, a croupier at the roulette wheel, waitresses at the bar, but no customers. I tried to look at their feet, but couldn’t get the right angle. I pointed to what looked like a blackjack table. “We go there?”

“No,” he said, and aimed us toward a door in the back that I hadn’t noticed. “We go through there.”

The only sounds as we made our way toward the door were my footsteps. Every dealer’s, every waitress’s, every bartender’s head swiveled to follow our progress, but nobody spoke, and nobody smiled, and everybody was gray. I thought of being here, by myself, for years on end, with my voice the only sound, nobody talking to me, always winning no matter what I did, every hand, every spin, every bet. Collecting colorless chips by myself. Forever. I shivered a little, and Harry put his arm around me, but no warmth came from him. I guess you need a body for that.

We went through the doors, away from those silent gray watchers, and down a long, dim hallway. At the end of it, we went through another door and found ourselves in a small room. In it was a woman, a woman with long black hair pinned up in an elaborate crown. She had color. Black hair, pale skin, paper-white, blood-red lips. Like a fairy tale. And an evening dress that sparkled like rubies. Probably had them stitched into the beading, if I knew anything about evening gowns, which I did.

She smiled at me and instinctively I dropped my eyes to her feet. They were birds’ claws.

“I, um—” My voice sounded harsh in the silence. “I hear you have a game to play.”

The lady nodded and gestured to a small table, a blackjack table set up for two. “I do.” Her voice didn’t sound harsh at all, smooth as silk. Smooth as honey. “The question is whether it’s a game worth playing.”

“For Harry’s soul,” I confirmed.

“Yes.” She paused. “But what do you have to offer to make it worth my while?”

I took the chips out of my pocketbook, but the lady just looked bored. I took off my rings and added them to the pot, and they were good quality, believe me, my Phil can afford the best and that’s what he gets me, but she didn’t waste a second glance on them.

“I don’t need your money or baubles,” she said.

I drew the jar of raspberry jam out of my pocketbook. “I have heard,” I said, “that you like jam more than just about anything,” and I placed the jar on the table. The jam inside was a rich red through the glass.

At that, she gave a tinkling laugh, like a breeze shimmying through a crystal chandelier. “I do like jam,” she agreed. “Especially raspberry. But not more than anything. No, I’m afraid you have only one thing of interest to me. A soul for a soul, that’s how it is. You understand.”

“My soul?” I asked.

“Did he not tell you that?” She shook her head mockingly and wagged an admonishing finger at him. “So untrustworthy. Unreliable, that’s what I say. Well, once a con man, always a con man.”

I turned an outraged stare on Harry. “You should’ve said.”

He glanced away. “I thought you might not come,” he muttered.

I thought briefly about turning around, following the pull of my sleeping body right back to my hotel room. Then I thought about Myra, how she used to laugh when Harry twirled her in the air. She had been happy, before he left.

“I’m here,” I said grumpily. “We might as well play. But if I lose, you don’t get my soul until my grandchildren are grown. I’m betting my soul, not my life.”

“Of course,” said Lilith. “That’s reasonable.” She gestured for me to sit down at the table, so I did. “Put your valuables away, Mrs. Greenspan. We’ll play. Mr. Valenofsky’s soul against your soul.” She paused. “And the jam. Three hands. I deal.”

The first hand was over quickly with me getting an ace and a queen at the first deal. One for me.

The second hand didn’t go so well. Dealer started with a nine and a ten. She stayed, of course. I had a four and an eight. I asked for another card and got a two.

“Hit me again,” I said.

The card she gave me was a jack. “Bust.”

I started to feel a little dizzy as she shuffled the cards for the final hand. The little room seemed to expand to the size of a stadium, and I felt eyes on me, even though I couldn’t see anyone else there.

“You should’ve asked me to play her at poker,” I muttered to Harry. “Or canasta. There’s too much chance involved in blackjack.”

“Nah,” said Harry. “I’ve seen you play before. This is your game. You clean up at blackjack.”

I didn’t know how to explain to Harry that to clean up at blackjack you had to keep track of which cards had been played, that the odds got better the longer you played, that three hands was more or less chance.

I like Vegas to visit, but I really didn’t want to spend my afterlife here. I hadn’t even been sure there was an afterlife until a couple days earlier, but now that I knew there was, I wanted to spend mine with Myra and my parents, not in some washed-out gray casino by myself, or worse, with Harry.

Lilith dealt again. I looked at my cards. They were both sevens, so I turned the hole card face up and split them. “Double down.” The next cards I got were a five and a nine, so twelve in one hand and sixteen in the other. Nowhere near close enough, especially when Lilith took one card, and face up she showed a six and a ten.

“Hit me.”

A ten and a five. I wondered what would happen if we both hit twenty-one. In most casinos, draws go to the dealer, and that wasn’t me.

“Bust,” I admitted on the twenty-two hand. “But I’m staying in the other.”

Lilith turned over her hole card. It was a four. I turned over mine. “I win,” I said. My voice sounded strangely calm, but I knew I was terrified. It was like I was observing everything from some distance.

“So you do.” The demoness sounded amused. “And so you keep your own soul, for whatever awaits it, and you can have Mr. Valenofsky’s as well. Hold out your hand.”

I did, and she dropped gold-colored casino chip into it. It had Hebrew writing engraved on it in a spiral, but it was too small for me to read even with my glasses.

“Thank you,” I said. It didn’t seem like enough. “Please take the jam, though. As a gift.”

Lilith’s eyes lit up—literally, they glowed orange for a moment—and she smiled. “Many thanks,” she said. “I do love jam.” She opened the jar and dipped in her finger, and licked it clean. “It’s good jam. Mrs. Greenspan, I’m sure you’ll find the right thing to do with the soul. Mr. Valenofsky, you may accompany Mrs. Greenspan back through the mirror in the main room. Good night to you both.”

I tucked the golden disk into my pocketbook. We retraced our steps back to the gray casino and through the mirror into my bedroom, Harry beaming like he’d just won a million bucks. When we got back into my room, I lay down and eased myself back into my still sleeping body. I felt so tired.

“Go wherever you want, Harry,” I said. “Just don’t be here when I wake up.” Then I closed my eyes and fell into a dreamless sleep.

When I woke up the next morning, though, my pocketbook was beside me on the bed, I was still wearing the good dress I had worn to Yenne Velt (I’d forgotten to take it off when I rejoined my body), and Harry was sitting in the room’s easy chair.

“What are you still doing here?” I asked. “You’re free. So go be free. Go do whatever it is you should be doing.”

He shook his head. “I can’t, Josie-Jo. I tried. I can’t go more than a room away.”

“Away from me?”

“Away from the poker chip.”

“So what you’re saying is, I should flush that thing down the toilet,” I said.

“You’ve always been so grumpy in the mornings,” he said. Then he looked a little worried. “Please don’t do that, though.”

I remembered Lilith telling me I’d find the right thing to do with it. She hadn’t mentioned toilets.

“Go in the other room while I get dressed, then. I’m flying home today. I guess you’re coming with me.”

I wasn’t sure what I’d expected to happen after I helped Harry, but him hanging around me everywhere I went because I had some kind of oversized magic subway token wasn’t it. Go, I told him, be free, take the poker chip and go on to whatever Adonai has in store for you. I tried to put the chip in his hand, but it just fell right through.

He was with me on the plane back to NYC, in the taxicab home to Sutton Place, and in the bedroom while I unpacked. I didn’t like it. I had lived a pretty good life without him for thirty years, and I wanted it back.

“C’mon, it’s not so bad, is it, Josie-Jo?” he coaxed. “We always meant to spend our lives together, didn’t we?”

I rolled my eyes. “That ship sailed a long time ago, Harry. I want you gone. Now be quiet and let me think.”

“Josie—”

“I swear, if you don’t shut up, I’m gonna drop that chip down the next sewer grate I see.”

Harry never could keep his mouth shut, and I didn’t want him yammering at me on the train all the way to Philly, so I reached a decision.

“I’m putting the chip in the jewelry box in my bedroom,” I told him. “You can cool your heels here until I get back with the kids.”

“Aw, Josie, I want to see our grandkids too!”

I rounded on him. “You don’t have grandchildren, you understand me? I have grandchildren. Phil, he’s a good man, a good provider, he takes care of those kids, he has grandchildren too. You have nobody, you understand? You left.”

“I get it, Josie, I get it.”

“I’m not sure you do! You left, so you have nothing to do with Elsie and Danny. Nobody else has been able to see you since Vegas, so don’t you dare show yourself to my grandchildren now.”

“Our grandchildren, Josie, no matter what you say. And I can’t promise that—it’s easier for kids to see ghosts than adults. Their minds aren’t all cluttered up with garbage yet.”

That’s men for you. They do their little dance, and they think that makes them a father forever afterward. And then a grandfather. No. You gotta wake up every damn day and decide to do it, all day, and then do it again the next morning. Every morning.

“Yeah, well, I don’t want their minds cluttered up with your garbage.”

His tone changed to wheedling. “C’mon, Jo. It’s hard for me to make anybody who’s not family see me, y’know. I never remarried, not like you—”

“You never had to!”

“—you and those kids are all I have left.”

“What about your brothers and sister?” I snapped. “Can’t you go bother them?”

“Well, if I knew where they were, and you gave them the gold chip, maybe I could.”

We glared at each other for a minute.

“I don’t know where they are, either,” I finally said. “But I know where you’re going to be while I go get the kids.” I put the chip in the jewelry box and slammed its lid shut.

The next morning on the train, I had some time to myself to think. Harry couldn’t go on staying with me—when he walked out on me and Myra, he’d made his choice, as far as I was concerned, and now there had to be a way for me to make mine. I could just toss the poker chip into the nearest gutter when I got home, of course, but, eh, I couldn’t bring myself to settle on that. Myra would’ve hated me for it. She loved her father so much, or the memory of him, anyway.

I knew I was out of my depth, was the thing. But I wasn’t sure what to do. Phil would think I was off my rocker if I started babbling to him about ghosts and Las Vegas. Our rabbi at the synagogue on East Fifty-first Street . . . well, he’s a nice young man, a macher in the making, really, but I’m not sure about something like this. This is more of a . . . private matter. A personal trouble, and that nice young man, he might just write me off as a crazy old woman. That’d be no good, not for me, and not for the kids.

Trains are good places for thinking, but it wasn’t until I was on the way back, with Elsie reading the new Oz book I’d brought her on one side of me and Danny slumped against me snoozing on the other, that it came to me. All of a sudden, I knew exactly who to go to for advice, and she wouldn’t think I was crazy, either.

A few hours later, we were walking through the apartment door, Danny still half asleep and stumbling. When we got inside, his head shot up in surprise and he blinked furiously.

“Who’s that, Nana?” he asked.

I followed his gaze into the shadowy hallway in time to see Harry melt into invisibility.

“There’s nobody here but us, sweetie,” I said. “Zayde won’t get back from his business trip for another week.”

“I could have sworn I saw someone,” he said. “Didn’t you see somebody, Elsie?”

Elsie was so deep in her book that she didn’t even hear him.

“Maybe you were dreaming,” I said, and ruffled his hair. “You two go in your rooms and unpack, and afterwards we’ll have dinner. I made chicken paprikash and dumplings yesterday, and it’s waiting in the icebox.”

I went to my bedroom and closed the door quietly. Harry was waiting with a hangdog expression on his face.

“What’s the big idea?” I hissed. “I told you not to let the kids see you! What’s Danny going to think?”

Harry held up his hands. “Hey, hey, I didn’t hear your key in the lock until it was too late, that’s all.”

I glared at him anyway.

“Say, though, those are some kids, aren’t they? The girl with her head in a book, she keeps reading like that, she’ll go far. I guess she does well at school, doesn’t she? Better than I ever did, I bet.”

“They both do well,” I said coldly. “They’ve got smart heads on their shoulders.”

“I knew it!” he said. “And good-looking, too. The boy even has my curly hair. Cute kids, both of them.”

“You can try to butter me up all you want, Harry,” I said. “I don’t care. Tomorrow we’re going to see a witch.”

The next day I made breakfast for the three of us, gave the kids some money for a double feature, and sent them out the door. Then I took the gold poker chip from my jewelry box and put it in my pocketbook.

In the elevator, I pushed the little white button, so the doorman had a taxi waiting when I walked out the door. He opened the door for me to get in and shut it firmly behind me. Harry drifted right on through. Nobody but me noticed.

I gave the driver an address on Delancey Street and the car started moving downtown. Harry seemed lost in thought.

“It’s not that old d—”

I shot him a warning look.

“That old . . .” He seemed to struggle for words and finally shrugged and resorted to, “That froy vos hot lib froyen.”

“Tante Deborah,” I said. “Yes.”

He looked annoyed. “She never liked me.”

“She doesn’t like most people,” I said. “In your case, she was right.”

“What’d you say?” asked the driver.

“Nothing,” I said. “I was just talking to myself.”

The rest of the journey was silent.

The apartment on Delancey was above Tante Deborah’s brother-in-law’s appetizing shop. I heard the shop had done so well that he owned the whole building now. In fact, the shop did so well that they could’ve moved uptown if they wanted, but Tante Deborah wanted to stay in the old neighborhood. The apartment was a walk-up, and at my age that wasn’t easy. I don’t know how Tante Deborah or Tante Ruth, her constant companion, managed it. Still, they’d been living there together as long as I could remember.

When I knocked on the door, it was Tante Ruth who opened it. She smiled. “Josie, it’s so good to see you, you should come visit more often.”

She brought me inside and hugged me. Henry drifted in after me, but she didn’t notice him. I gave her the banana cake I’d baked the night before and brought with me (I bake very good banana cake, the best, actually, and I’m not telling you my secret).

The apartment was a nice one—not modern like mine and Phil’s, of course, but nice, with plenty of light.

Tante Deborah was sitting at the kitchen table. She didn’t get up when we came in, which could have been her age—getting up is not easy at my age, let alone hers—or could have been her general grumpiness, but she did smile briefly at me before her dark eyes refocused on a spot just behind me. On Harry.

“Josephine,” she said. “And you brought your shande of a late husband.”

“Ex-husband,” I said, just as Tante Ruth, rummaging in the cupboard for another teacup and plates to put the pieces of banana cake on, looked over her shoulder at me and sighed.

Harry managed to look confused and offended at the same time. “How—” he began.

“She’s a witch,” I told him. “And you are a shande.”

Tante Ruth bought over tea and cake, and we all ate and chatted. I asked after Ella, their niece, maybe seven or eight years younger than me. She’d gotten her politics from Tante Ruth, worked as a labor organizer for years, and married an Irishman she’d met doing that. They had a couple of kids, teenagers by now. It was only when the cake was gone that Tante Ruth cleared the plates from the table and refilled our teacups. Tante Deborah stirred a spoon of cherry preserves into hers.

“Well, I’ll give you two a bit of privacy now. I’ll be in my office in the back, working on a story. Give a shout if you need anything.” Tante Ruth cheerfully left the room.

Tante Deborah stirred her tea and scowled. “Does she think I can’t get us more tea and cake if we want it?” she muttered, but without much conviction, only habitual annoyance. Then she refocused on me. “So, Josephine. Why is the ghost of that shande you made the mistake of marrying following you around like you were newlyweds again?”

“I won his soul at blackjack, Tante,” I explained. “And now I don’t know how to get rid of it.” I took the golden disk from my pocketbook and handed it to her while I told the whole story. She examined it closely, rummaging in the kitchen drawer for a magnifying glass at one point, and listened.

“The jam was a good idea,” she said, peering at me through her cat-eye glasses. Then she looked down at the disk through the magnifying glass.

“Can you read it?” I asked.

“Of course I can read it,” she said irritably. “I’m not so old that I’ve forgotten the holy tongue. I’m just so old that I can no longer see it so well.”

She mused over the disk a bit longer and then shot a sharp look at Harry. “Chaim ben Meir is you, I take it?”

Harry nodded.

“Well,” said Tante Deborah. “I want to talk to Josephine about this privately, so, Chaim, I’m going to put you away for a while.”

Harry looked confused, and I wondered if she was going to pitch the disk out the window (Harry was right that she had always disliked him particularly—she despised gangsters, big-time or small), but all she did was leave the room briefly and return with a small, carved wooden box. She slid the top off, placed the golden disk inside, and slid the top back on. As soon as the box was shut, Harry disappeared.

“How—” I began, but she waved the question away curtly.

“What you have to figure out, Josephine, is what you want to do. He’s tied to this chip, you know that. If all you want is to be rid of him, you could pitch it in the East River. So the question is, why haven’t you?”

I opened my mouth to answer, but nothing came out, and all of a sudden I didn’t know the answer.

“Well,” Tante Deborah continued. “You have a few options here. If you still love him so much you want to keep him around, all you have to do is hang on to the chip.”

“I do not love him,” I said, almost as annoyed as Tante Deborah usually sounded. “I haven’t pitched him in the river for Myra’s sake. Same reason I helped him to begin with.”

“Ah, Myra.” Tante Deborah looked momentarily sad. “Does he know?”

“He knows she’s dead, yes.”

“Ah.” Tante Deborah went on. “If you think Myra would want you to send him on to whatever awaits him—and no, I don’t know—then what you have to do is smash the chip.”

“Smash it how?” I asked.

“Smash it how? How do you think? A hammer should get it done.”

“But it’s—”

“It’s Bakelite, is what it is. Bakelite with a shine on it.”

“Do I need to bless the hammer? Carve Hebrew into it?”

“No,” she said. “But you can if you like. It won’t hurt anything.”

“What’s the third option?” I asked, out of curiosity.

“You can leave the chip here with me. I’ll keep it in my box, and he’ll stay snuffed out.”

“Destroyed?” I gasped. “That’s cruel.”

“Contained,” she said. “And if you ever wanted him back for anything, you’d know where to find him.”

“Back from where? Where is he right now?”

“In the box.”

“Like a genie in a bottle?”

“More or less.”

“I don’t think Myra would want that,” I said, after thinking for a moment.

Tante Deborah shrugged. “Well,” she said. “It’s up to you. Just make sure you know what it is you want to do. And why.”

I nodded. “Thank you,” I said. And then, “May I have the chip back now?”

When Tante Deborah slid the lid of the box back, Harry appeared again. He looked shaken and didn’t say anything to me as I hugged Tante Deborah good-bye. We were on the street and I was trying to find a taxi before he spoke again. There weren’t many cabs that far downtown, and I had just decided to give up and take a bus when he asked, “What was that box?”

“How should I know?” I answered.

He was quiet again until we got to the bus stop, and then, “So, what did the old witch say to you, anyhow?”

“Nothing you needed to hear,” I said.

I thought a lot about that box that afternoon while the kids were out, mostly because I wanted Harry to shut up and stop chattering at me while I figured out what I wanted to do.

I didn’t still love him, did I? That wasn’t the reason I hadn’t thrown the chip into the East River, was it? I didn’t think it was. I didn’t love him. I had loved him, but that was a long time ago, before he abandoned us. It was Myra I loved, Myra I would always love, no matter how mean she had been. Myra and now Elsie and Danny, too. Myra would never forgive me if I threw her father’s soul in the river. She was the one who loved him, even though he didn’t deserve it and never had. She’d been so much like him in some ways, charming and vivacious.

I thought and thought. And in the end, I knew what to do. I left the golden chip in the jewelry box and went to the hardware store, and I came home with my purchase tucked in my pocketbook.

“Tomorrow,” I told Harry. “Tomorrow after the kids go out to play, you and I are going on an outing. I don’t want you here when my Phil comes back at the end of the week.”

“You know how to free me?” asked Harry, all excited, all happy, like this was some kind of game and he’d just won.

“Sure,” I said. “All I have to do, Tante Deborah says, is smash the chip.”

“Then what are we waiting for?” he asked petulantly.

“There’s something I want you to see,” I told him.

Then I heard Elsie’s key in the lock and that cut off whatever whining he might have been about to start.

The next morning, I put some spending money in Elsie’s pocket and took the kids to visit Sadie. We had a cup of coffee together, and I told them I had some chores I had to do and that Sadie should put them in a taxi back to me in the afternoon. I came home, put on my most sober spring coat, and slipped the golden disk into its pocket. I picked up my bag and a dark gray umbrella that matched the coat. “Let’s go,” I told Harry.

“Right with you, Josie-Jo. Where we going?”

“You’ll see.”

I pressed the white button in the elevator again, so the doorman had a taxi waiting for me by the time we got to the door. It had started to rain, and he held his umbrella over me as I walked from the door to the yellow cab. Not a drop got on me. Of course, the rain fell right through Harry.

“A long trip today,” I told the cabbie. “I’m going to Mapleton. Washington Cemetery.” I gave him the address.

“A cemetery, Josie?” Harry smirked at me, a smile I’d once found very attractive. “Who died?”

“You did,” I reminded him. “It’s the right place for you. Now shush, I don’t want the cabbie to think I’m nuts.”

We rode in silence the rest of the way.

When we got to Washington Cemetery, I paid the cabbie and told him that I wouldn’t be long, and that if he waited for me, there’d be extra for him on the way back.

He nodded. “I gotta go back to the city to get another fare anyway, lady. Might as well take you with me, and make something off the trip.”

Harry and I walked into the cemetery. I led the way until I found what I was looking for.

“Here,” I said. “This is Myra’s grave.” I took a rock from my pocketbook, a pretty one I’d found in Central Park with the kids a while ago, and put it on the headstone. The headstone still looked new. Well, it had only gone up a few months before. The rain pattered on my umbrella as Harry examined the stone.

“Poor kid,” he said, and he sounded sad. “You never told me what happened, she got sick?”

“She killed herself, Harry.”

I listened to the rain on my umbrella for a few seconds before going on.

“She never got over you leaving. She was never the same afterwards. She was happy for a while after she and Siggy got married, but when he left her, too . . .”

I trailed off, and Harry didn’t fill in the silence. I didn’t want to say the next part, but I forced myself to go on.

“She wasn’t a good mother, especially after Siggy left. I knew, but I didn’t want to know, and I let it go on. She screamed at them, she wasn’t there when they needed her. She drank and she took pills. She blamed Elsie for . . . I don’t know, just for being, I guess. She was a bad mother, Harry. Elsie was running the house by the end.”

He opened his mouth, but didn’t say anything, and after a moment he shut it again.

“One weekend, she’d asked me and Phil to take the kids, and when we brought them back on Sunday, she was dead. Elsie and Danny found her, Harry. They found their mother’s body. Alcohol and sleeping pills.”

“It couldn’t have been an accident?” he asked softly.

“No. She left a note. And it wasn’t the first time she’d tried.”

“What did the note say?”

“It was addressed to me,” I told him. “Not you. And it was mean, like poison. Mean to me, mean about Elsie. I burned it. For over a year now, I’ve wondered if what she said was true, if I was the reason she was so . . . unhappy.” I paused for a minute and stared at a tree a ways away. That’s a trick I know so you don’t cry. “Phil and I took the kids to live with us. Best for everyone that way. So that’s what happened to your daughter, Harry.”

“It’s not your fault,” he said, softly again.

I exhaled and then drew another, deeper breath. “No,” I agreed. “It’s yours.”

Harry looked like the slap I’d aimed at him back in Vegas had finally landed. “What?”

“It’s your fault. After you left, she couldn’t be happy again, she didn’t know how. You know, every city she ever travelled, she checked the phone book for your name? I don’t know what she was gonna do if she found it, show up on your doorstep? She told her friends you were a dancer, on tour with a musical, when she was a kid. I think sometimes she believed it. She would’ve given anything for dance classes when she was little, but we couldn’t afford it until it was too late.

“She never got over your leaving, Harry. She never stopped waiting for you, hoping you’d come back.”

I took another deep breath. “So this is where I’m leaving you,” I said. “So if she comes back to this spot, if she comes back to her body, the way you hung around the Starlight in Vegas? You’ll be here, waiting for her. And then maybe she’ll finally be happy again.”

I folded my umbrella and dropped to my knees. I took the trowel I’d bought at the hardware store out of my pocketbook and began digging a hole, small but deep, in the sod of Myra’s grave.

“What?” Harry burst out. “What? What are you doing? Aren’t you going to smash the chip? Smash it!”

Instead, I took the chip out of my pocket and dropped it into the hole I’d made. I began filling it back in.

“Don’t do this, Josie. Smash it. Let me go free. Don’t leave me here! Don’t do it! There’s no one here, it’s as gray as the casino was! There’s no one here to talk to, nothing to do! I’ll go out of my mind!”

I stood up and brushed the dirt from my skirt. “Don’t be silly, Harry,” I said. “I come to visit every few months. Once or twice a year I bring the children. You’ll get to see them grow up. Over time. I’ll even leave a note for Elsie in my will, telling her about you, about the chip. She can dig it up and smash it then. If she wants to.”

“Josie! Don’t do this! It’s not too late, you can still dig it up again! Don’t go—don’t leave me here alone!”

“It’s been good to catch up with you, Harry. I did always wonder what had happened to you. I’ll see you in a few months.”

I put my umbrella back up and turned to walk back to the waiting taxi.

“Don’t you walk away from me!” Harry screamed. I turned back to look at him as his face contorted into a snarl. “You goddamned gold-digging bitch. You heartless cunt! You’re as bad as that old dyke you call tante!”

I drew into my coat and shivered. For a minute he had looked and sounded just like Myra during one of her bad spells. But my voice was steady when I replied. “You didn’t have two pennies to rub together when I married you, Harry. I married you for love. And I wasn’t the one who left when things looked bad.

“Good-bye, Harry.”

I could still hear him screaming furiously after me when I got back to the cab, and I was too keyed up to sit still in the cab. I had to smoke a cigarette and pace for a few minutes to calm my nerves before we started back to Manhattan, but the cabbie didn’t mind. I told him to go ahead and run the meter while I paced.

“He’s not happy, huh?” the cabbie asked.

“Huh?” I said, and stopped walking in circles. I figured I must’ve misheard him.

“The guy you were with. The ghost.”

“You . . . knew he was with me?” I asked.

“I need glasses to read now,” he said. “But I still see all kindsa things.” He lit a cigarette too, and there was a companionable silence.

“No,” I finally said. “He’s not. But I wasn’t happy when he left me, either.”

The cabbie nodded. “You can’t let the dead run your life,” he said. “Eventually, you gotta leave them behind.”

When I got home, I felt exhausted. I took a bath and then put on a housedress, much lighter and brighter than the dress I’d worn to Myra’s grave. I had a light lunch and took a nap.

I woke up a little before the kids got home and I made myself a cup of tea. I put out two plates of cookies and two glasses of milk and a deck of cards. I also brought out a dish of jelly beans. Then I sat and sipped my tea and waited for Elsie and Danny.

When the door opened, I felt ready for them. I hugged them both and brought them over to the table.

“I love these cookies!” said Danny, munching away.

“Good, my darling,” I said. “And when you finish eating the cookies, we’ll use the jelly beans to play a game. Nana’s going to teach you both how to play blackjack.”

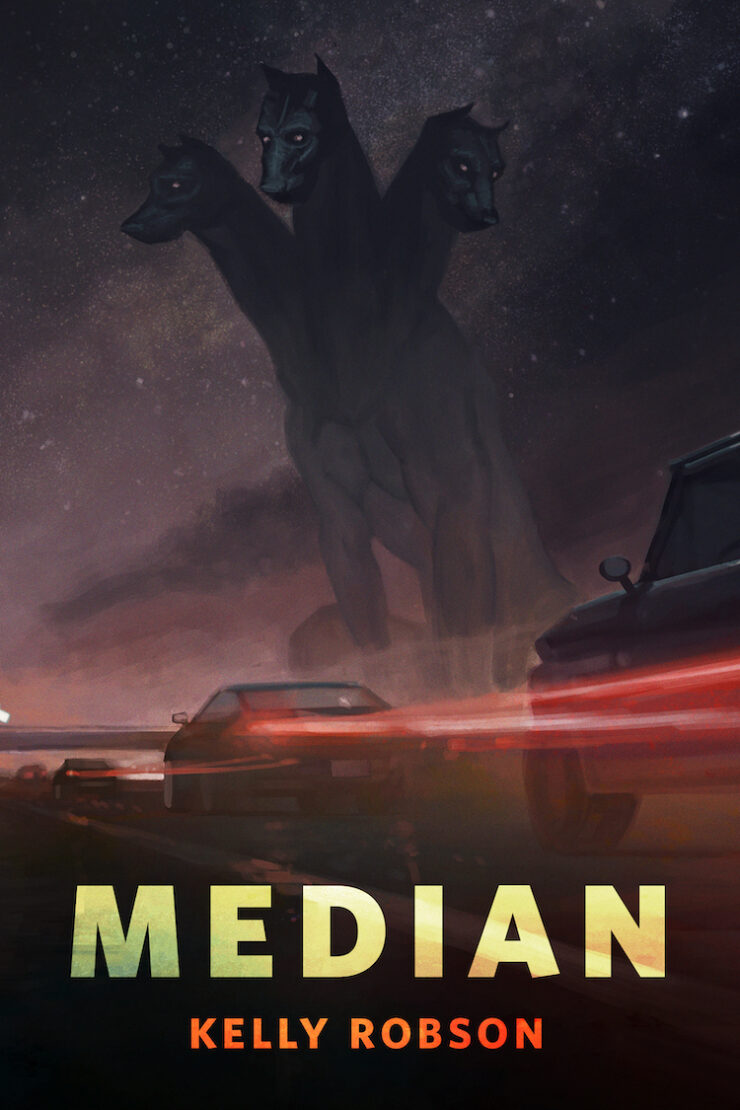

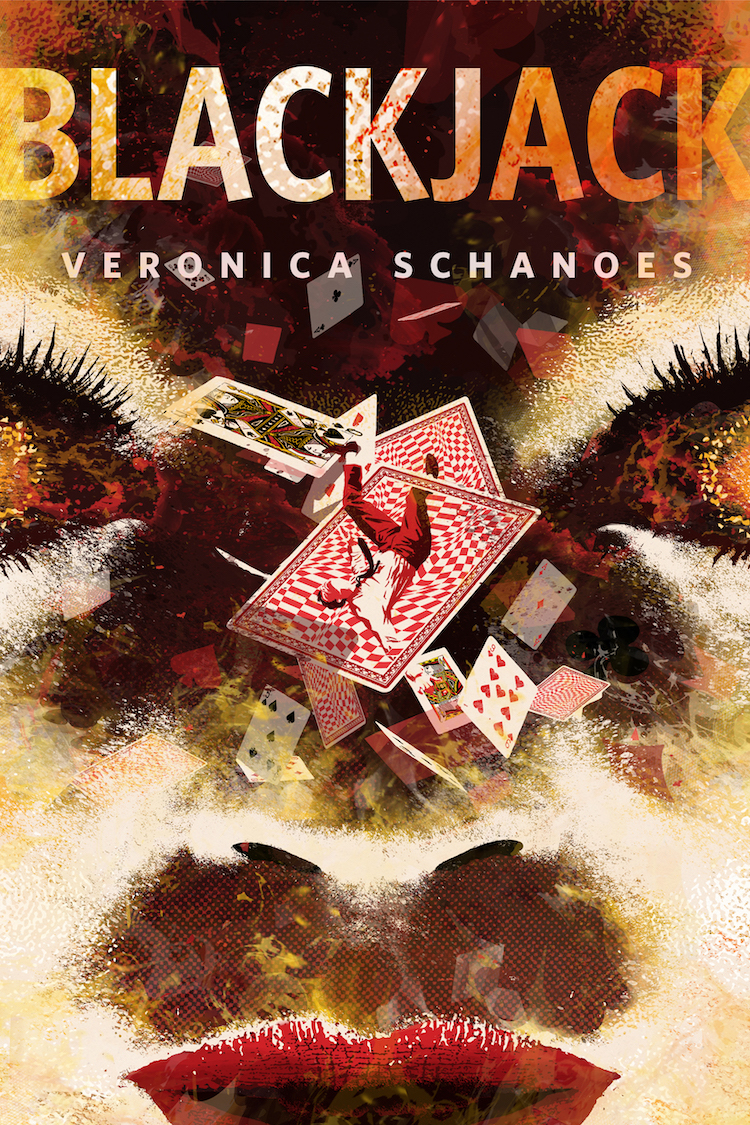

“Blackjack” copyright © 2024 by Veronica Schanoes

Art copyright © 2024 by Mark Smith

Buy the Book

Blackjack