Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

This week, we start on J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, first published as a serial in The Dark Blue from 1871 to 1872, with the Prologue and Chapters 1-2. Spoilers ahead!

“She is gone without so much as conjecturing the nature of her illness, and the accursed passion of the agent of all this misery.”

Prologue

The following narrative is taken from the posthumous papers of Dr. Martin Hesselius, the famous occult detective. Hesselius attached a “rather elaborate note” and a reference to his Essay on a subject involving “some of the profoundest arcana of our dual existence, and its intermediates.” Since the editor means “simply to interest the laity,” he includes no abstract from the “learned Doctor’s” work. Such is the “conscientious particularity” of the lady who wrote the narrative that it can stand on its own.

The editor hoped to reopen a correspondence with the lady, but she had died. Probably she would have had little to add to her already-careful record.

Part I: An Early Fright

The narrator, Laura, describes her Styrian castle home. Her father, an Englishman, has retired from the Austrian service on a pension, but in their “lonely and primitive” locale even a modest fortune can purchase an estate.

The isolated castle is protected by a moat and drawbridge. The nearest inhabited village is seven miles away, but three miles westward is a ruined village whose church contains the tombs of the now-extinct Karnstein family.

The castle’s chief inhabitants are nineteen-year-old Laura and her aging father. Her Austrian mother died in her infancy. Two governesses, Madame Perrodon and Mademoiselle De Lafontaine, complete their table. Visitors are few.

Laura’s first memory is an early fright that left a long-lasting impression on her mind. She was six years old, abed in her nursery, when she woke to find neither nurse nor nursery maid; she was about to loudly protest this neglect when she noticed she wasn’t alone after all. A young lady with “a solemn, but very pretty face” knelt beside her bed. As Laura watched in “a kind of pleased wonder,” the lady lay down and embraced her, smiling. “Delightfully soothed,” Laura fell asleep until woken by the sensation of two needles piercing her breast. She cried out, and the lady started away, as if to hide under the bed.

Servants reassured Laura she’d had a nightmare after finding no intruder or wound. But the housekeeper noticed a still-warm hollow in the mattress next to the child. The servants sat up with Laura that night and every subsequent night until she was fourteen. Not even her father could comfort her, nor the nursery maid’s story that it was she who lay beside Laura—Laura knew the strange woman hadn’t been a dream.

A more effective visitor than her physician was an old priest who prayed with her. He had Laura repeat “Lord hear all good prayers for us, for Jesus’ sake;” for years after, this would be her daily petition.

Part II: A Guest

One summer evening Laura (now 19) and her father walk in a neighboring glade. He tells her that a much anticipated visitor, General Spielsdorf’s niece Bertha, has died. Perhaps Spielsdorf’s mind has been deranged by grief, for he writes that Bertha’s “illness” was actually the doing of “a fiend who betrayed our infatuated hospitality.” He’ll devote his remaining years to “extinguishing a monster.”

Buy the Book

And Then I Woke Up

Though she never met Bertha, Laura’s disappointed and disturbed. She and her father join the governesses in viewing the moonlit scene. Madame Perrodon muses romantically about the full moon’s “magnetic influence,” while Laura’s father admits to a sense of impending misfortune, the cause of which he can’t pinpoint.

Nature’s tranquility is shattered when, on the road that passes the castle, they see a hard-driven carriage hit a rise and turn over. One passenger, an older woman in black velvet, is unhurt; the other, a slender young lady, lies unconscious by the roadside. The castle party hurries to the accident scene, where the older woman is bemoaning the fact that her daughter must now be too injured to travel, even though their journey is a matter of life or death! The older lady cannot pause to await her daughter’s recover, nor return this way for a full three months.

Laura urges her father to shelter the young lady until her mother’s return. The mother, by her manner a person of consequence, agrees to the arrangement after a whispered conference with Laura’s father. She gives her still-swooning daughter a hasty kiss, climbs into the righted carriage, and drives off at a furious pace.

This Week’s Metrics

The Degenerate Dutch: Even isolated in the Austrian boondocks, there’s no need to “include servants, or those dependents who occupy rooms in the buildings attached to the schloss” in the list of one’s potential company.

Libronomicon: Laura is never permitted to read ghost stories and fairy tales. Maybe if she were, she’d be a bit better inoculated against midnight visitors. Her father does, at one point, randomly quote The Merchant of Venice, so she’s not entirely without imaginative literature. Presumably Hamlet is a no-go, though.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Mademoiselle De Lafontaine waxes lyrical about the full moon’s effect on lunacy and nervous people, in the course of which she gives a startlingly clear description of a cousin who had a stroke (probably not actually caused by the full moon under which he was sleeping).

Anne’s Commentary

The ruling truism about real estate is that a property’s value rests largely on location, location, location. I propose a parallel truism about fiction in general and weird fiction in particular: It’s all about setting, setting, setting. All right, not all about, but the more consistently a story is set in a specific location (real or imagined), rendered in specific and vivid detail, the more it immerses readers in a world as opposed to plopping them in front of a stage. A stage separates the audience from drama and action, explicitly admitting all this fuss isn’t real. A world, implicitly, is real. You can live in a world.

Metaphorically, per Shakespeare, all the world’s a stage and all the men and women merely players. Also, life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player who struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more. So why should fiction aspire to the feel of reality? I don’t know, maybe because if the world is a stage, then the stage should be the world. Maybe while those players are strutting and fretting around, we should for the duration of the play believe in them.

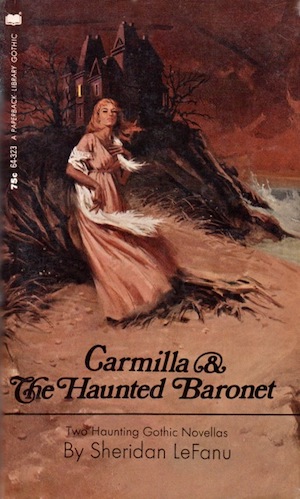

If we can believe in them after the play is over, all the better. That’s a damn good play, or a damn good story. Like Carmilla, one of my favorites since I first read Le Fanu’s novella in this 1987 DAW anthology:

By forthright (pulpy-naive?) eighties standards, that is a fetching cover. I’m not crazy about the castle in the background, which in its generic stylization rather supports my opening argument. The oversized moon, similarly meh. Ditto the Halloween Superstore Dracula cape and bat-brooch. But it’s all redeemed by the lady’s lean-and-hungry aspect and her mesmeric stare. As the come-on above the book title says, she is needing your blood and craving your soul. There’s no indication which of the anthology’s vamps she represents, but I think of her as Carmilla, after the infatuated Laura has been playing with her dark tresses for a while. The sensuous specificity with which Le Fanu describes this hair-play belongs, however, to a chapter beyond our current scope.

His description of Laura’s castle and its environs is smack dab within that scope; in fact, it takes up a good chunk of Parts I and II of the novella, and to excellent effect. Though his effusions go on far too long for the regulation realtor’s blurb, I’m ready to fork over a down payment on his blissfully remote, charmingly Gothic estate. It’s got the many-windowed and towered schloss, the perilously steep bridge, the picturesque glade and stream, the vast and shadowy forest. And the moat, “stocked with perch, and sailed over by many swans, and floating on its surface white fleets of water lilies.” Much classier than a swimming pool!

As for the abandoned village within walking distance? I am drooling on Le Fanu’s fictional-estate-for-sale listing. Sure, he doesn’t claim the village is haunted, but I can read between the lines. Roofless church, desolate chateau, the moldering tombs of an extinct family with a name like Karnstein? The eternal forest lowering over it? My weird-seeking antennae quiver ecstatically.

And they keep quivering, as Le Fanu doesn’t confine his opening chapters to eerie travelogue and atmospherics. The Prologue prepares us for the uncanny by revealing that the narrative comes from the personal uncanny archives of Dr. Hesselius. We’ve met him previously in “Green Tea,” the story that opens Le Fanu’s collection In a Glass Darkly with eclat, as Carmilla closes it. Part I gives us Laura’s “early fright,” which if it isn’t a dream must be—what? A premonition? Or, as I’m thinking, Carmilla’s psychic visit to the child rather than her visit in the full undead flesh. A semi-visitation, you might say? Energetic enough to warm a hollow in Laura’s mattress but not material enough for to leave a bite mark?

Part II brings in General Spielsdorf’s letter, unsettling enough in its announcement of Bertha’s death, doubly so in its seemingly unhinged assertions that a “fiend” did the girl in after entering the General’s house in the guise of “innocence” and “gaiety.” The “monster” betrayed the General and Bertha’s “infatuated hospitality”—given that Laura and her father are about to extend their hospitality to a presumed innocent, ought we not recall Dad’s vague presentiments of disaster? Also Madame Perrodon’s fancy that the moon lights up the castle windows to “receive fairy guests.”

In modern popular imagination, fairies have gossamer wings and sunny temperaments—look for their images and porcelain effigies in any gift shop. But in our more primal imagination? Wings or no wings, a fairy’s most pertinent feature might be teeth.

Teeth, perhaps, like needles.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Much like Lovecraft’s work, Carmilla is a piece that I didn’t read in college, but which shaped a shocking amount of my nerdy experience. It was a favorite of my then-gamemaster-now-householdmate Jamie, and shaped his Vampire: The Masquerade games to the point where I once played out several hundred years of the life of Not-Countess-Karnstein without ever reading her foundational literature. (Jamie also once fostered the aptly-named Kittens Karnstein, who managed to draw a fair amount of blood even with minimal teeth.)

I finally got to Carmilla five years ago, flipping forward to see what all the fuss was about after having a mixed reaction to “Green Tea.” On starting my second read, my Lovecraftian attraction-repulsion remains. Attraction: everything is better with lesbian vampires, not to mention isolated castles and moonlit vistas and young women who are as thirsty for company as… others… are for other things. Repulsion: Hesselius remains annoying even when we’re spared “the learned doctor’s reasoning,” and adds to the aura of melodramatic artificiality of the whole setup. And, you know, I’m not reading a book from 1872 in the expectation of avoiding melodrama. I just want the idiot ball to be more consistently invisible. In an ideal world, I also prefer the author to consider lesbianism, as such, less inherently terrifying.

But still: lesbian vampires. Everyone appreciates a good sexy vampire, right? Or an un-sexy one, depending on the decade—vampires in all their incarnations are a staple of horror. They tend toward the more orderly sort of horror, being prone to over-punctilious attention to manners and predictable reactions to symbols of the prevailing religion. But they’re also the sort of horror that lurks just outside thinly protected boundaries, something that can catch you if you slip up on the rules or open the wrong door just once. They can also pull you over the line, changing who you are and what you want, making you into a creature of the outer darkness. And they can come in creepier and more fungous flavors depending on the nature of that outer darkness.

Of course, that darkness looms closer in some places than others. Laura’s father illustrates nicely the perils of moving for cheap housing. Sure, there are places where you can buy a nice house for a dollar, as long as you don’t mind the complete lack of economy, social services, or functional local government. And there are places where you can buy a castle for a dollar, as long as you don’t mind your daughter growing up desperate for companionship, and also don’t mind the vampires.

After moving to an isolated castle with picturesque ruins nearby, Daddy further compounds his error by “studiously” avoiding any stories that might give his darling daughter nightmares, or make her jump at shadows. Kids who grow up surrounded by dark woods need instruction books, but poor Laura must make do entirely without.

He’s terrible at sharing bad news, too. “I quite forgot I had not told you,” really? Then right after reading about the fiend who betrayed the General’s infatuated hospitality, he utterly fails to be suspicious about the whole, “Alas and alack, I must abruptly leave my child with you for several months, let us not bother with introductions” setup. To be fair, Laura is suspicious but goes along with it anyway in the interest of making a friend. Which is, again, one of the issues that’s likely to come up when moving your family to an isolated castle.

Next week, in honor of its appearance on the Locus Recommended Reading List, we peek back into When Things Get Dark and find Seanan McGuire’s “In the Deep Woods; The Light is Different There.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden comes out in July 2022. She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.